Celtic Spirit Animal: The Humpback Whale

Humpback whales are bards and mystics of the depths. Their songs call us back to our primordial home where there is no beginning or end, no self or other, no gain or loss, no life or death. Their serenity and strength bear witness to the fruits of that return. Returning home, we do not dissolve without remainder into the void. We are not sedated or paralyzed by it. We are rejuvenated, recreated, and resurrected by it.

Owing to their resonance with our oldest and deepest self, humpback whales have captivated humans since time immemorial. They figured prominently in myth, with their roles ranging from malevolent to heroic. Without the technology to research these creatures in detail, whales eluded the ken of our Celtic ancestors. Save for the ones that occasionally beached or shocked sailors with a breach, little was known of them for millennia. Yet despite their ignorance, Celtic mythology captured their symbolic range.

Aloof. Benevolent. Violent. Always cloaked in mystery. Emissaries of the otherworld. Bards of sea and spirit.

Humpbacks serve as ideal guides and inspirations for artists, mystics, or those longing to reconnect to their primordial home - the One. Below, I will describe the humpback whale’s natural and mythic lore, outline its elemental associations with water and earth, and explain its key symbols. This information will allow a Celtic pagan to tailor their practice to this singer of the depths.

Nature Lore

Appearance: Humpback whales are one of the larger whale species, reaching lengths of up to 19 meters and weighing in at 40 tons. To put that weight into perspective, that’s 25 Teslas swimming through the sea at 30km/hour. Humpback whales have a distinct appearance with long pectoral fins, a knobby head, and bumps on their upper and lower jaws called tubercles. Barnacles also attach to humpback whales, giving them their iconic mottled appearance and doubling as weapons when fending off predators.

Long-Distance Migrations: Humpback whales undertake some of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling up to 16,000 kilometers round trip between their breeding and feeding grounds. The European humpback whale population summers in Iceland and Norway and winters in Cape Verde. They can be spotted in Ireland and England during autumn as they migrate south.

Acrobatic Displays: Humpback whales are a whale-watcher favorite due to their impressive acrobatic displays, which include breaching (leaping out of the water and crashing back), tail slapping, and fin slapping. For observers, they’re just plain cool, but they also serve various purposes, including communication, attracting mates, removing parasites, and having a good time.

Singing: Male humpback whales produce complex and haunting songs that last up to 20 minutes, with the longest recorded lasting 22 hours. These songs consist of repeated patterns of sounds and play a role in mating rituals and social interactions. Each population of humpback whales has a unique song, but they are known to integrate other populations’ songs into their own and innovate on their own. The result is an ever-evolving tapestry of sound.

These songs can travel up to 1,400 kilometers underwater and are unique enough that other whales can identify their singer. Underwater sound pollution severely disrupts humpback whale behavior, with sounds even 200 kilometers away sometimes driving them from plentiful hunting grounds.

Feeding Behavior: Humpback whales are baleen whales, which means they filter-feed on small fish and krill. They sometimes use a feeding technique called bubble net feeding, in which a group of whales works together to encircle their prey by blowing bubbles in a spiral pattern, creating a “net” of bubbles that traps the fish. Then, the whales lunge upward with their mouths open, engulfing water and prey.

Social Behavior: Humpback whales are socially complex creatures. They often stay in large groups called pods while migrating, with some pods reaching upwards of 20 members. The social group is critical when a mother’s caring for her young, as baby humpback whales are easy prey for predators, such as great whites or orcas. Escorts, often males looking to mate with the mother, follow the female for long stretches and drive off any potential threats.

Breeding: Humpback whales’ mating behavior defies their pacific nature. During breeding season, male humpback whales compete for females’ attention in heat runs. To understand what a heat run is, imagine a dozen 35-ton whales charging at each other at full speed underwater, slashing at each other, breaching, and singing with their prospective female in tow. It’s a kinetic and mesmerizing theater of violence.

Once a female has chosen a mate, humpback whales engage in a courtship ritual involving lengthy and elaborate displays. This includes breaching, spyhopping (raising their heads vertically out of the water), and body rubbing. After mating, the female gestates for around 11 months and gives birth in warm tropical waters. The mother will spend the next year feeding and protecting her calf.

Conservation Status: Humpback whales were once severely depleted due to commercial whaling, but significant conservation efforts have helped their populations recover. Today, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUNC) classifies them as a species of least concern.

Myth Lore

It is difficult to comment on whales in general in Celtic mythology, let alone the humpback whale. Although the Celts were a seafaring people, it’s difficult for 21st-century pagans to realize how mysterious and elusive whales were. To get a taste of this mystery, I invite you to imagine yourself as a fisherman fishing out of Galway a thousand years back.

You’ve been sitting out on the sea all day, the familiar coast in the distance, when all-of-a-sudden you see a 30-ton something breach 20 meters from your dingy. Strange bumps cover its face. Bright white barnacles run along its belly. The waters explode, and you hear the smack of this leviathan against the sea. Its spray covers you and your brother-in-law and sends your dingy rocking back. Terrified that this great beast might have you in its sights, you make a hasty retreat back to Galway.

As your dingy glides through the choppy waters, you look behind to see a few more humpbacks breaching and sending up plumes of seawater. One trails you for some way, peeping up from the waters one last time before vanishing.

After a frantic journey back, you finally return ashore, unsure of what you saw, where it came from, and its intentions. It becomes another story to add to the tapestry of local legends recounted in the taverns and beside hearths.

The mystery of whales might seem hyperbole, but it’s not. Whales have eluded understanding for most of human history, save for small pockets of sea-based peoples.

The earliest record of whaling in Western Europe is in Southern France in the 11th century. Even then, whaling was a little-known industry and took centuries to spread throughout Europe. Even while they were hunted in small numbers, whales remained a mystery. Europeans didn’t know that the whales they hunted migrated thousands of kilometers from Western Africa. They didn’t know that the sperm whale could spend upwards of two hours underwater hunting giant squid in the ocean’s depths. They knew the simple facts needed for hunting, killing, processing, and selling the whale. Outside of these facts, whales were an enigma that would take centuries to understand.

Talking about the humpback whale in Celtic paganism is impossible because the Celts didn’t know the different types of whales. Instead, I’ll look at whales’ role in Celtic mythology in general. When we look at it from that perspective, a surprisingly clear picture emerges of the whale as a figure of mystery, ferocity, and kindness.

Sailing to the Otherworld : Saint Brendan and The Voyage of Mael Duin

Some of the earliest recorded Irish tales are immram, or voyage tales. These stories, with fragrances of The Odyssey, recount a company’s journey into the world beyond. The older of the two accounts we’ll look at, The Voyage of Mael Duin, tells of Mael Duin’s voyage to avenge his father. After snooping around, Mael Duin meets a druid who reveals his murderers’ location: they’ve holed up on an island deep in the Atlantic. The hero gathers warriors and launches on his voyage to this mysterious island. After witnessing many horrors and wonders, including salmon raining down from the sky, birds singing psalms, and a vicious horse-like monster, the company finally discovers the island. Here’s the kick: the journey has so transformed the warriors that the two groups make peace instead of taking revenge.

In The Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot, influenced by The Voyage of Mael Duin and the oral immram tradition lost to history, the story follows a similar pattern yet is adapted to match the Christian spiritual-warrior ethos sweeping through Ireland. The tale begins with a holy man, Saint Barinthus, recounting his journey to the Promised Land. Inspired, Brendan finds this island for himself and gathers a group of monks to join him on his journey.

Saint Brendan and company visit dozens of islands over seven years in their search for the Holy Land, coming across pillars of crystal, demons hurling fire at the earth, and a Judas freed from hell by God. In one of the iconic encounters from the tale, the monks stop on a large rocky island to make camp. However, as they light the fire, their “island” begins to shake. Brendan tells his companions that this “island” is, in fact, Jasconius, the largest whale in the ocean. The terrified company rush back to their ship and speed away, the fire still burning behind them.

After more trials and tribulations, the monks’ ship is swallowed by a giant frog in which the Promised Land awaits. They spend the next 40 days wandering this paradise without wants before they’re forced to leave due to Brendan’s impending death. The monks hurry back to their Irish monastery, share their tale, and shortly after, Saint Brendan dies a hero.

In both of these tales, the ocean is a place of mystery, wonder, danger, purification, and, ultimately, salvation. Exactly how influenced these tales were by their Christian scribes will never be known, but since other immram tales locate their final destination in the unquestionably pagan otherworld (Tir na NoG), it’s likely that this was a pre-Christian motif.

Although the whale makes only a brief appearance in The Voyage of Saint Brendan, it’s a significant one. This tale would be translated into dozens of European languages and become one of the most popular tales of the medieval period. The image of the massive whale during their quest was an image that would find its way into literature for the following millennia. Its appearance reinforced its ancient association with the otherworld and what the sea journey represented: mystery, danger, wonder, purification, and salvation.

Savior from the Gods: Jonah and a Scottish Cinderella

A modern Cinderella tale down to us from Donegal at the turn of the 20th century.*1 The story’s essentially a retelling of Cinderella. Two elder sisters abuse their younger sibling and force her to do all the work. A fairy godmother who magically dresses her and finishes her chores. A charming prince who falls in love and eventually wins her hand. But there are a few uniquely Celtic and pagan elements worth lingering on.

First, the tale differs from many other tellings in its brutality. Once the prince finds his Cinderella (named Critheanach, in this case), his work isn’t yet done. He must defeat nine of the greatest champions of that land before he can claim her as his prize. He defends himself for nine days by killing all nine challengers before finally going to Critheanach’s father to ask for her hand in marriage.

Another departure is that the other sisters aren’t married off to other suitors or simply ignored. One of Critheanach’s older sisters, Gael, mistakes her other sister for Critheanach and murders her by throwing her off a cliff. When Gael discovers her error, she tricks Critheanach into returning to the same spot and shoves her off the cliff to her death. When Critheanach reaches the stormy waters, though, a massive whale rises up, swallows her whole, and safely holds her in its belly.

Meanwhile, Gael returns to their lodging. She pretends to be Critheanach and tries to sleep with her sister’s new husband. The prince suspects something’s aloof and rejects her advances, demanding they both sleep on separate sides of the bed. The next day, the prince gets word from his shield-bearer that Critheanach has been swallowed by a whale and will only be released once it’s struck on a red spot on its underside. The prince ventures into the stormy waters on a skiff armed only with his javelin. When the whale breaches, he throws his spear and pierces the animal in its red spot. The whale then vomits up Critheanach onto the boat and flees.

When the couple returns to the castle, they discover the sister’s murder and punish Gael for her wickedness. The sentence and fate are worth quoting:

So judgment was passed on Geal. She was cast out to sea on an offshore tide in a small rowing boat, but without oars. She was given enough food and water for a night and a day and left to the fortunes of Manánnan the great sea god. It is said by some that she was dragged beneath the waves and became a slave to the Kelpie. Others said that she managed to reach the shore of Lochlann and married a king’s son there and made him unhappy ever afterwards.

What’s curious here is the unvarnished paganism. Gael is put to the mercy of Manannan, not God. Additionally, she might have been enslaved by the Kelpie, a race of underwater water-spirits. While this might seem surprising, a look at the folklore and beliefs of the period in books like the Carmina Gadelica and Yeats’s Celtic Twilight reveal a blend of paganism and Christianity which ranged from antagonistic to seamless.

In Gael, Donn, and Critheanach, the whale alludes to the story of Jonah and the whale. In that Biblical tale, Jonah is thrown overboard by his crew members to stop a storm from harassing them. It works. The storm relents, the sailors are saved, and Jonah himself is swallowed whole by a whale. While stuck in the whale’s stomach, Jonah repents for his wrongs and asks for forgiveness. On the third day, God orders the whale to vomit Jonah up. From there, Jonah continues his quest.

While the whale is a benevolent figure of divine intervention in both cases, there’s an important distinction in the later Celtic tale. In Gael, Donn, and Critheanach, the whale isn’t some pacific agent of the Lord, but a beast capable of violence. The whale flies into the air and crashes into the water attempting to wreck the prince’s tiny skiff. The whale also doesn’t offer up Critheanach out of deference for the Lord, but because of a grievous wound afflicted on it In this Celtic tale, the whale is a personification of the ocean itself. Vast, ferocious, mysterious, intimately with the otherworld, and benevolent in its own inscrutable and frustrating way.

Moby Dick and the Leviathan: A Force of Nature

Herman Melville’s ancestry has roots in Scotland and Ireland and his literary sources shared a similar lineage. Milton. Shakespeare. The Arthurian legends. Maritime folktales which drew heavily from England and Spain. Add to that the classics, like The Odyssey and the King James Bible and you’ve got yourself an epic.

The “villain” of Melville’s magnum opus is Moby Dick, a mysterious, massive, magnificent, and fierce whale. The captain, Ahab, devotes his life to capturing this beast. After much struggle, hardship, and sacrifice, Ahab fails. The beast escapes and kills everyone, including his hunter. Only Ishmael survives to tell the tale.

Moby Dick is a rich, multifaceted symbol that evades easy definition. On the one hand, he represents truth, goodness, and glory, and Ahab represents the all-too-human hubris of trying to subordinate these forces to our own will. But this creature of the deep also recalls the primordial Biblical meaning of the Leviathan: the indomitable power of nature. Despite the crew's clever schemes and efforts, the beast triumphs and puts man back in his proper place.

The Leviathan of the Bible is a symbol of the chthonic chaos, violence, and darkness that underpins existence. The Bible bears many influences from Greek and Near Eastern mythology, with many scholars drawing parallels between the Leviathin myth and other local mythic traditions in which a primordial monster must be vanquished to establish order in the universe. Examples can be found in the Canaanite story of Lotan and the Babylonian myth of Marduk slaying Tiamat.

Melville’s departure from this mythical trope represents a modern Celtic twist on this ancient myth. Unlike in the Bible and the myths which influenced it, in Moby-Dick, the leviathan wins and god, man, loses. Here, the natural world is not subjugated to a rational king above, but is a chthonic force that must continuously be struggled with and eventually lost to.

The Harp of Ireland

The final story worth sharing from the Celtic corpus is about the origins of the Irish harp. Can Cludhmor had a heated argument with her husband which ended with her storming from the house in a huff. Hoping to cool her head, she walked along the midnight coast and listened to that old familiar song of the sea. As she was walking, she heard an enchanting tune carried on the wind. She followed the sound, hoping to find it, but was lulled to sleep on the coast midjourney. When she came to, she discovered the rotted corpse of a beached whale. As the wind passed through the sinew and bone, an enchanting sound sang across the land. Forgetting her marital troubles, she decided to craft an instrument to recreate its sound. The result was the Irish harp.

While we’ll never know for sure, I believe this myth was inspired by the humpback whale, famed for its beautiful song that humans can hear above and below water. True or not, this tale gives mythic precedence to the humpback whale’s association with music and the harp in particular.

The myth also aligns with the whale’s connection to the otherworld. First, Can Cludhmor is famed for inventing the harp and was also worshipped as a goddess of music and dreams. Second, in most ancient cultures, including Greek and Celtic, dreaming was not turning off the brain but a portal to the beyond. Can Cludhmor made that journey asleep on the beach before her discovery, a connection that ancient Celts wouldn’t have missed.

Another way to travel to the otherworld in Celtic myth was through voyages across the sea, as in the stories of Brendan and Mael Duin. The tale also hints at another means of travel: the ecstasy of music. Recall that music called Can Cludhmor through the night, put her to sleep, and led her to the discovery of the harp. Music is a vehicle for crossing the ocean of the known to arrive at the otherworld, a role shared by whales.

What the Can Cludhmor myth reveals is that whales are not only fierce forces of nature but doorways to the divine, emissaries of the mystical world beyond the ken of the known and the familiar. The pairing with music is also significant, as it confirms that the pathway to the otherworld is not through hard reasoning but, as in Brendan, a bold leap of faith, purification, and the ecstasy of contemplation.

Elements: Water and Earth

As we’ve seen in the facts and tales above, humpback whales are complex creatures. They are powerful, intelligent, artistic, social, mysterious, and intimately connected with the beyond. Although ancient Celts had little direct knowledge of these creatures, their characterizations hold up rather well. As I'll explain, even the view of whales as violent threats to human civilization makes sense when seeing them as representatives of the chaotic, chthonic force of the natural world.

Water

Amid all of these complexities, their strongest element is, by far, water. This might seem obvious, given that they’re marine mammals, but the water element is about temperament, not habitat. Water symbolizes connection, softness, and tranquility, all things the humpback excels in.

One of the most remarkable qualities of the humpback whale is their gentleness and tranquility. Sure, they might fight over mates or fend off predators at times, but otherwise, they live unchallenged in the sea. This dominance gives their presence a serenity lacking in creatures lower in the food chain, like anchovies, chickens, or lamprey, who must be on constant alert for food and predators.

Humpback whales are carnivores that survive off of huge daily catches of krill and fish, but they have a markedly different style from tigers or hawks. Eagles, for example, have a spear-hunting style. Success depends on swift, violent action. Humpbacks, on the other hand, have a fishing hunting style. They follow their prey, open their mouths, and let come what may. There is none of the struggle and violence found in an eagle as they hold down a trout and rip out its guts.

Humpback whales’ interactions with non-predator or prey species confirm their gentleness. There are multiple cases where humpbacks saved divers from sharks and aided non-humpback whales under attack. Whale watchers also love them due to their playful nature, sometimes approaching vessels and breaching against the water.

Despite their friendliness, humpbacks are primarily solitary creatures. They might travel in pods during migrations, while finding mates, or to protect calves, but they spend most of their life alone, feeding and relaxing in the waters they call home for the day.

With their unique, creative songs and complex social structures, they’re also a symbol of connection, not only to each other but also to the otherworld. In the story of Can Cludhmor, the whale’s song brings the frustrated wife into the dream world and is the genesis of the harp. For the Irish, the harp was not only a musical instrument, but it also accompanied poets. Through a poet’s songs and verses, the world of The Book of Invasions was painted, the past was revived, and new heroes were made. Another connection between whales to the otherworld comes in their appearance in the immram of Saint Brendan, purifying and readying the monastics for paradise, or as servants of God in the Book of Jonah or the faeries in the tale of Gael, Donn, and Critheanach.

Earth

Earth is the secondary element associated with whales due to their grounded nature and chthonic associations. Their groundedness has already been touched on above, but it’s worth repeating. As an apex species, they face no foes and live like the snails of the ocean - slow, serene creatures who quietly go about their life. They sometimes show off their physical prowess, but that’s the exception. Spending even a few minutes with these giants of the sea, their groundedness is palpable.

The second association is that found in Moby-Dick, the Bible, and other Celtic myths: the whale’s chthonic power and rage. The chthonic association is factually correct. Humpback whales are creatures of the depths. They spend most of their time underwater, often diving for long stretches in search of food. They are about as close to an alien as earth can offer, save for the creatures of the deep ocean. Even their mottled, barnacled skin recalls their intimacy with underworld.

Their association with rage, though, is weaker but not without truth. Humpback whales are famously docile but also have the potential for violence. There are many reported cases of ships being capsized or damaged by grumpy humpbacks, with some of these accidents proving fatal. Humpbacks also can fend off dozens of ravenous orcas or sharks with strikes of their tails and fins. When mating season comes around, get ready for 30-ton whales smashing into and slashing at each other at full sprint.

This primordial fear of the sea and its titanic masters, whales, contributes to their long-standing association with power and rage. Moby-Dick and the Bible, drawing on Near Eastern and European myths, portray the whale as a symbol of nature's chaotic, volatile, indomitable spirit. In both tales, the whale rebels against the ordering of god and man. In the Bible, God reigns it in and subjugates it to his rule. In Moby-Dick, Ahab attempts the same but fails and is killed instead. In my opinion, the association with nature’s rage is primarily not due to the whale’s behavior but its unmistakable connection to the sea and all it represents.

The last and most important association of the humpback whale is with mystery. These animals live and hunt in the depths of the ocean, a world nearly as alien to humans as the vast stars and space which enclose us. In this endless expanse of blue, the oneness of creation where all distinctions fall away. There, there is no beginning nor end, no here nor there, no self nor other. It is here that the humpback makes its home, and it is here that the humpback whale serves as a representative.

We see this mystic link most clearly in Saint Brendan’s journey to paradise. In the tale, paradise is depicted in material terms. The absence of pain. An abundance of food. Security, ease, and beauty. For contemplatives, the paradise depicted symbolizes union with the divine and a return to the One, where all sorrow and want evaporate in the light of god.

Humpback whales are otherworldly creatures who call us back to the original, undifferentiated waters that are the source of life. Their serenity and haunting song remind us of the spiritual depth, power, and vastness within and without. Their domain is not the psychedelic ecstasies of the visionary but the undifferentiated union of the mystic. They are grounded, serene, and gentle, tempered by ferocity when provoked.

These creatures are suitable for Celtic pagans seeking the depths of themselves and life, uninterested in the pretty colors and powers that occultism or worldly success offer. This journey to the depths, though, is not like the explosive flight of the eagle or the charge of the bear. It’s the quiet, graceful descent of a 40-ton whale into the endless blue.

Artists, mystics, or those who feel called to the divine and serene are prime candidates for the humpback. While these creatures can create enchanting pieces of beauty and lure us into the wonders of the ocean, the humpback whale’s work is largely a solitary endeavor that relies on the pull of the void to draw them into its depths and consume them. As the tales of Brendan, Ahab, and Jonah remind us, this journey is not easy. It is full of temptations and dangers that can destroy those who dare. Only a seeker whose soul is purified of its dross, whose endured marvels and horrors, whose risen again and again after failure and failure will set eyes on paradise.

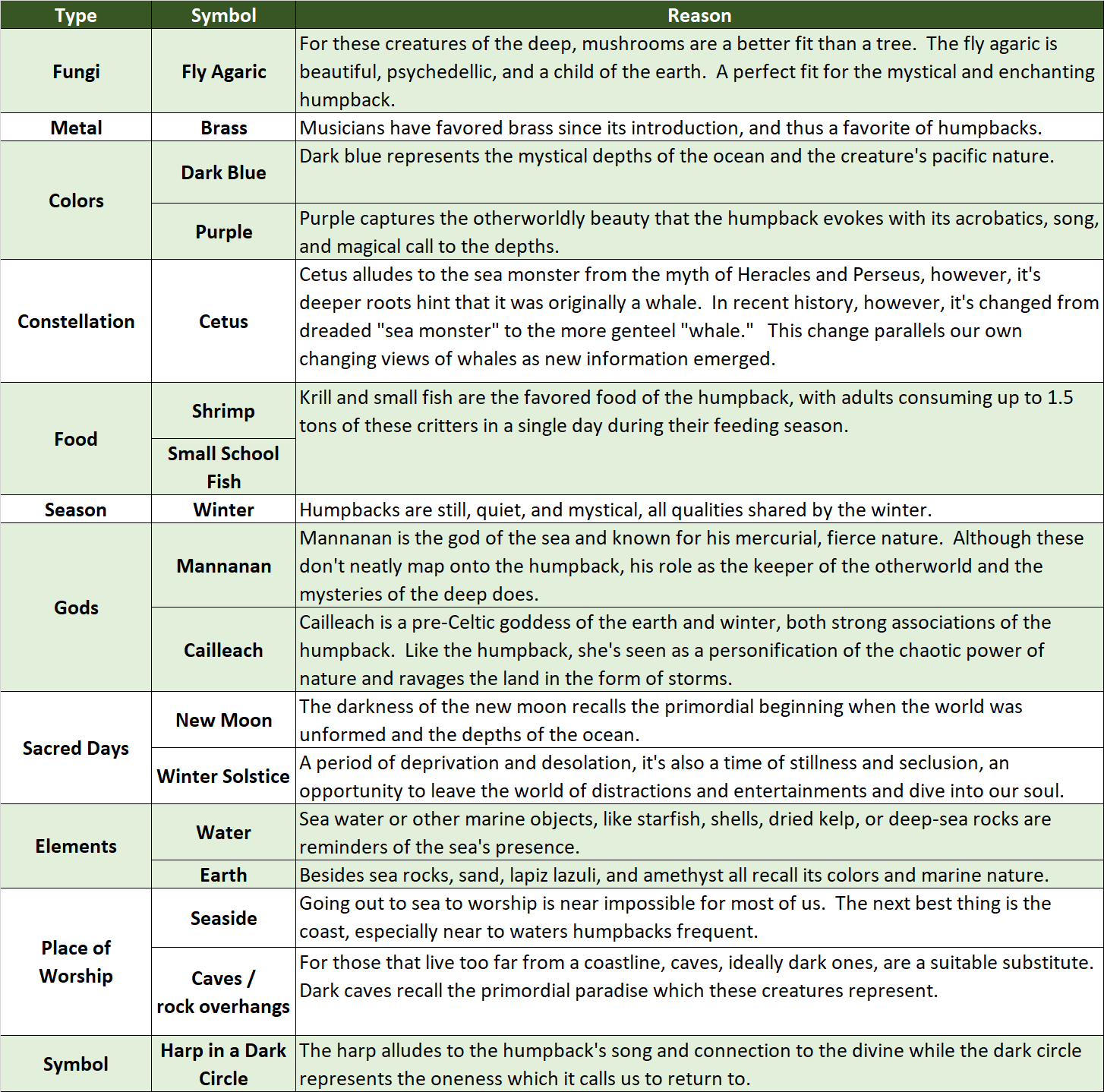

Associations

Below is a chart of the eagle’s associations across a variety of categories. The chart is particularly handy as a reference for other practices, such as rituals, art, or meditations.

References

- Ellis, Peter Berresford. The Mammoth Book of Celtic Legends and Myths. London: Constable and Robins Lmtd, 2002.