Celtic Spirit Animal: The White-tailed Eagle

Mighty. Violent. Serene. The eagle is sky’s king. He rules by force, cunning, and stillness. His images can be found on sacred vessels and weapons the world over. In European paganism, he accompanies the king of the gods, Zeus and Talanis, in their rule over heaven and earth. He is lord.

But, as with the other kings, he has his pale. He is not as wise as the salmon, not as otherworldly as the owl, nor as sly as the fox, nor as brutal as the bear. The eagle’s role is as visionary, sovereign, and warrior. With these qualities, the eagle is the ideal companion for leaders working in the complex, ruthless world of business, politics, or war. We can also apply his qualities in other situations, such as in relationships, spiritual growth, or healing. However, the eagle does best in his territory, where calculation and force triumph over all else.

Below, I will describe the eagle’s natural and mythical lore, outline his elemental associations with fire and earth, and explain his key symbols. This information will allow a Celtic pagan to tailor his practice for this king of the sky. For advice on how to work with spirit animals, I will provide a basic structure later.

Nature Lore:

Appearance: The white-tailed eagle is massive. Their wingspan reaches upwards of 2.5 meters across. They stand around 1 meter high and weigh in at 5kg. They have dark brown feathers and sport their iconic white tail. Males are slightly smaller due to their role as hunters, while females are larger due to their role as guardians of the nest.

Habitat: White-tailed eagles are found in various habitats, including sea coasts, lakes, rivers, marshes, and forests. Since they lack oils to protect their feathers from the water, they prefer to hunt in shallow coastal areas, as deep dives are risky. Some, like those in Russia, migrate hundreds of kilometers every year. Others, like those in Germany and Norway, settle in one place and never venture beyond their borders.

Diet: Their diet mainly consists of other birds. Since eagles are slower and less agile than much of their prey, they use a mix of surprise and tactics to hunt their prey. Eagles also eat fish, small animals, and carrion, especially in winter.

Behavior: White-tailed eagles can perch upright for hours and silently survey their territory while hunting. When they take flight, they usually fly low to not alert their prey. The white-tailed eagle is also fiercely territorial towards intruding adult males. This defensiveness is due to the vast stretches of land needed to survive, with many couples requiring around 100km2.Breeding: White-tailed eagles typically mate for life. They build large nests on cliffs or in trees, preferring the black poplar or willow, and lay 1 to 3 eggs yearly. After hatching, the female broods the eggs in the first month while the male hunts. Once the chick’s of age, both hunt and provide for the newborn until it leaves the nest during the summer.

Longevity: White-tailed eagles can live up to 25 years in the wild, although the average lifespan is around 20 years. In captivity, they can live even longer.Conservation status: The white-tailed eagle was once endangered in many parts of its range due to hunting, habitat loss, and pesticide use. However, conservation efforts have helped increase their population, and they are now considered a species of least concern by the IUCN (yay!).

Mythic Lore

As with all things Celtic, so much has been lost to the vagaries of history that it’s difficult to identify how culturally important the eagle was. Within the literary tradition of Wales and Ireland, the eagle appears only a few times and almost exclusively in connection with sovereignty and wisdom. In the material culture, eagles are a common motif related to war and the thunder god, Taranis. Given the paucity of evidence available, the best we can do is speculate from the surviving fragments.

The Welsh Tradition

Lleu Llaw Gyffes, a hero featured in the Welsh compilation The Mabinogion, has strong ties to the eagle. After nearly being murdered by his wife’s conspirator and paramour, Llue turns into an eagle and flees. Gwydion, the Merlin figure of the Welsh myths, finds the injured Lleu, lures him down, and heals him. Once fully recovered, Lleu reclaims his kingdom from the usurpers, slays his wife’s lover, and, with the aid of Gwydion, turns his treacherous wife into an owl.

In another Welsh tale, Culwch ac Olwen, the son of a powerful king, Culwch, goes on a series of adventures to win the hand of his love. During his quest, he must consult the four wisest animals to help him catch a wild boar. The eagle was the second wisest and oldest creature in the epic, second only to the Salmon of Llyn Llw.

In both tales, the eagle aids a to-be-king on his quest for the crown. In the first tale, the eagle serves as a protector and ferries Lleu away to safety before he can recoup and retake his rightful throne. In the second tale, the eagle transmits ancient knowledge necessary for the king to complete his quest, gain the hand of his love, and ready himself to succeed his father on the throne.

Ireland’s Seer: Fintan mac Bochra

The association of the eagle with wisdom appears again in the tale of Fintan mac Bochra, an Irish seer who arrived in Ireland with Noah’s granddaughter before the great flood. When the flood arrived, Fintan transformed into a salmon and fled to a cave called Fintan’s Grave. He then transformed into an eagle and hawk before returning to human form. In human form, Fintan served as the counselor of kings for millennia.

During his extraordinarily long life, Fintan was in the ears of countless monarchs and became the record keeper of all of Ireland’s knowledge and history. Given the brutish, violent, and short reign of kings (more akin to local warlords) throughout Ireland’s history, characters like Fintan represented the continuity of spirit and culture that allowed this fractious people to persist. Once he saw Christianity overtake his native religion and land, he left the mortal realm, never to return.

This story, an all-too-typical mish-mash of Christian scholastic rewriting and old myth, abounds in meaning, but for our purposes, it’s sufficient to point out that we again see the eagle’s association with sovereignty and wisdom, bested only by the salmon. While it might be the case that these myths share a common ancestral story, another possibility is that this ranking was a common formulation in Celtic culture. The supremacy of the salmon, which represented sacred wisdom, also confirms what both law and extant Roman tales tell of the Celtic structure: the druids and the sacred trumped the worldly power of kings.

Lugh, Odin, and the Eagle

According to H.R. Ellis Davidson in his book Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe, the eagle was primarily a symbol of both the sky and sovereignty, linked in various myths to the king of the pagan pantheon.*1 This association was likely strengthened by the Celts’ interactions with the Romans, for whom the eagle symbolized the Roman emperor and Jupiter, king of the gods.

Davidson also argues that Lugh and Odin are strongly linked to eagles. Although the two gods differ in many important ways, they also share many similarities. Both are gods of knowledge and skill. Both have a pair of ravens that act as spies and messengers. Both placed their centers of worship atop hills. And, importantly, both were claimed to be the ancestors of kings.

Lugh was the King of the Tuatha De Dannan and led them to victory over the Firbolgs. He’s known as a just, capable king whose long reign finally ends as the victim of a blood feud, a story that would have been all too familiar to an ancient Irish audience. In Lugh, we can see many strands of the mythic and symbolic role of the eagle coming to the forefront. The eagle in the myths thus far has been a source of guidance and protection. It is through the qualities of the eagle that a king can rule prudently and safely. However, that narrative is about to be disrupted in the untold tale of Taranis.

The Hidden Connection: Taranis

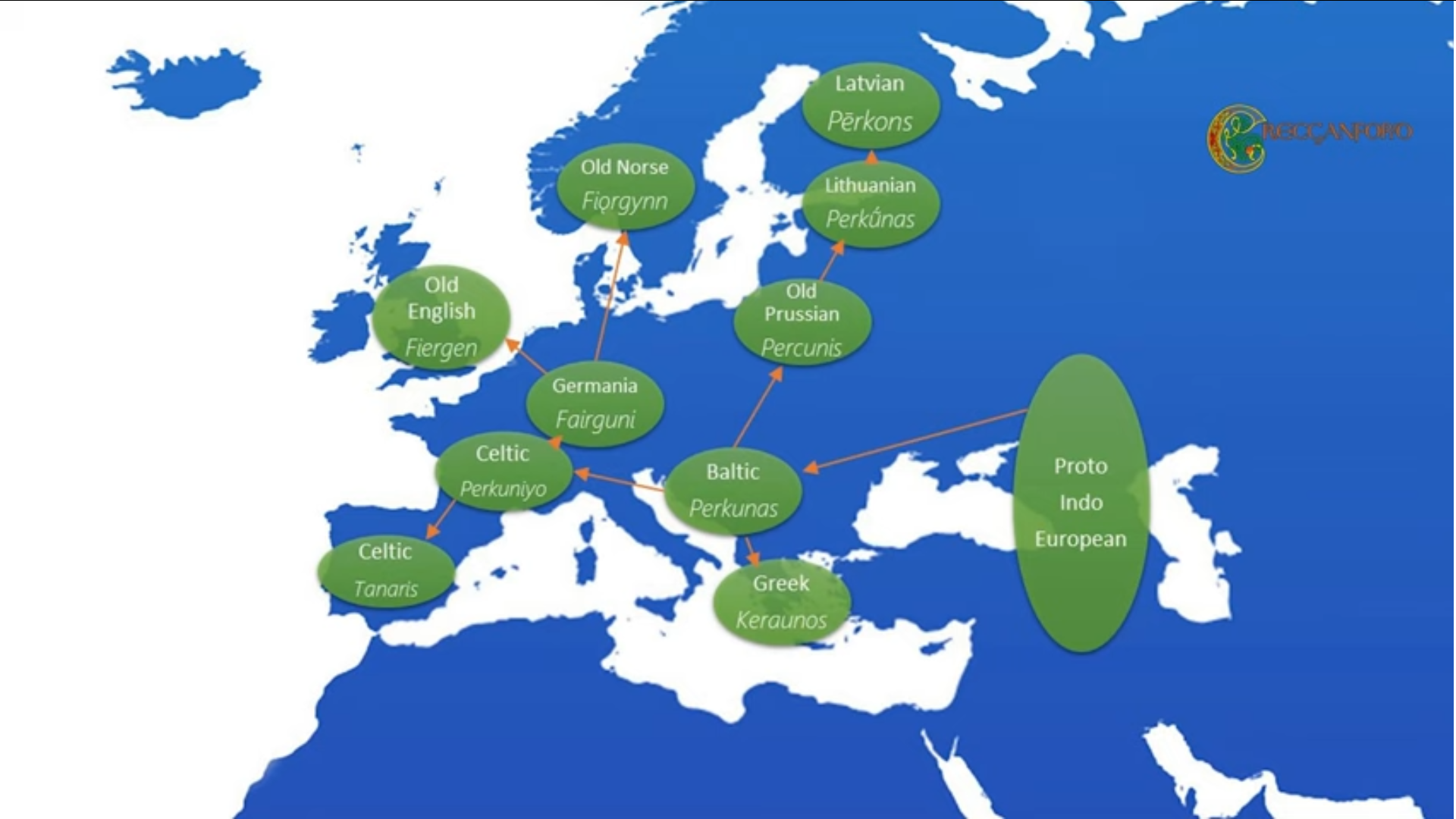

The strongest mythic connection of the eagle hardly appears within extant Celtic mythologies. This figure is the mysterious Taranis. His statues and icons can be found throughout Celtic lands, attesting to his popularity and importance. Yet, little else is known of him save for those images and his linguistic and symbolic connection to the ancient proto-European storm god.

Without getting into too much detail, Cracganford argues that the thunder gods of Europe all share the same source, attested to through the linguistic development of the first recorded appearance of the thunder god in the Balkans under the name Perkunas, which meant striker or thunder. The conflation of the terms is telling. This god isn’t a god of lightning alone but of violence and power. When this god moved south into Greece, he was renamed Keraunos, one of the older names of Zeus. When he moved west, he became Taranis, which means thunder in Celtic. And when he moved north, he became Fiorgynn, which eventually morphed into Thor.

The connection between these gods becomes clearer when you look at their iconography. They’re often pictured with a chariot wheel, an ancient symbol of the sky god, hold thunder in their hands, and are bearded and muscular. Compare the following two images below.

Although Thor wasn’t strongly associated with eagles, Zeus was, and later icons of Taranis also adopted the eagle as an emblem of the god. The connection between sovereignty, thunder, power, and the eagle is strong. Like Zeus and Taranis, the eagle is the king of the sky who swiftly and powerfully strikes down upon its prey. He is violent, inscrutable, and regal.Despite no surviving literary evidence, the Taranis-eagle connection is far stronger than with Lugh. There’s not only an abundance of surviving material evidence but also well-attested linguistic developments which connect Taranis to thunder, Zeus, and the eagle’s qualities.

This connection is even stronger when considering the eagle’s link with warfare in Celtic material culture. In many of the surviving Celtic arms, eagles often appear. This iconography strengthens the association with the warrior noble class, ferocity, and violence. While these two qualities might seem antithetical to modern sensibilities, for millenia, they were intertwined. In the days of the old gods, power was not ultimately won and maintained through diplomacy, trade, or virtue but through steel and blood.

Elements: Fire and Earth

The eagle’s primary element is fire due to his fierce, violent, explosive nature. Eagles are aggressive defenders of their territory and often fight intrusive males to the death to ensure they’re the only kings of their domain. Eagles are hunters who depend on violence, power, and cunning to survive. Outside of winter months, they ambush or grind down their prey before snatching and killing them, consuming upwards of 2kg of flesh per day. They might seem noble and serene in still photographs, but that image obscures their brutality. Watch them swoop down and catch a bird before tearing it apart on the rocks. They are raw power.

Another aspect of the eagle that figures widely in Celtic myth is wisdom. Fire is not just about power but also illumination and discernment. In the Culwch ac Olwen, the eagle is second only to the salmon in wisdom. In the tales of Fintan mac Bochra, the great sage took his second-to-last form as an eagle. While this association might seem odd to those unfamiliar with eagles, their hunting tactics demonstrate high intelligence. With ducks, white-tailed eagles feign dive to snatch them dozens of times until their prey is exhausted. After the duck is too tired to flee, they attack.

This wisdom also aligns with the eagle’s connection to sovereignty. Their intelligence isn’t like the raven's curiosity or the owl's otherworldly vision. The eagles’ wisdom is grounded in survival. A good king cannot be full of fancies or abstractions. He must be cold, cunning, and brutal. The eagle is that.

Another important quality of a king is vision and discrimination. Simply reacting to what’s happening leads to ruin. An inability to discern friend from foe, right from wrong, and potential from a dead-end is essential to navigating the trappings of power and wealth. An eagle’s unrivaled sight, matched with its high intelligence and violence, suits itself perfectly as an emblem of earthly leadership.

The eagle’s secondary element is earth. This association might be a surprise, as some might object it is nearer to wind. The eagle requires swift, violent action to hunt, and he sometimes migrates hundreds of kilometers yearly in search of prey. However, earth is a far stronger association for eagles. The first reason for this comes from mythology. These creatures have long been icons of sovereignty, which is first and foremost about land and earthly power. You cannot be a good king and live in the clouds. You must be grounded in the real. Feeding your people. Administering property and titles effectively. Protecting all from enemies without and within.

Also, behaviorally, eagles are not tempestuous creatures. The white-tailed eagle often sits on its perch for hours as it surveys its territory and waits for an ideal time to strike. It isn’t fidgety or restless but composed and serene. As a point of reference for a bird that’s a fire/wind temperament, look no further than the cock. Pugnacious yet fidgety and nervous. A cock’s nearly always moving - kicking up leaves, bickering with their fellows, jostling on branches or in the underbrush, starting fights, chasing hens. The eagle is not that. Like all apex predators, it sits in absolute confidence on its throne among the cliffs, observing until the right moment to strike. Then, an explosion of violence.

The earth element in the eagle represents composure, precision, practicality, and a preoccupation with concrete ends. Paying the bills. Keeping your family safe. Making sure everything’s squared away. However, that’s buoyed by the fire element: a strong sense of vision and purpose matched with cunning and explosive power to ensure success. It’s no wonder that Celtic and other European cultures have long associated kings and generals with this bird.

These qualities of the eagle are not limited to the battlefield or palace. A business owner, mother, or anyone else who finds themselves in a leadership position can draw strength from the eagle. A druid can also look to the eagle when they need both strength and street-smarts to deepen their connection to the divine. In relationships, we might call upon the eagle to bring clarity and decisiveness. It is up to our discernment to know the how and when of working with spirit animals.

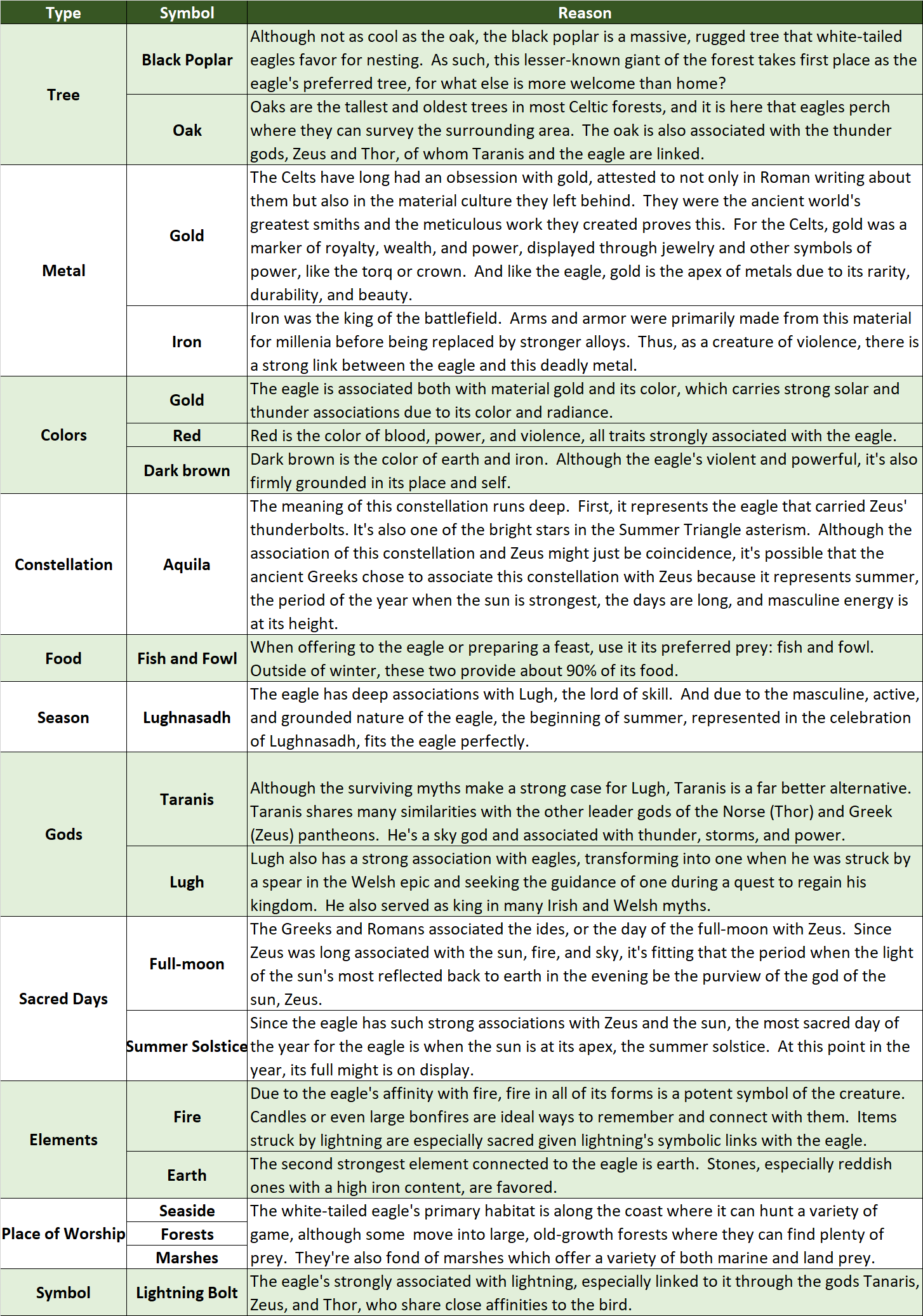

Associations

Below is a chart of the eagle’s associations across various categories. The chart is convenient as a reference for other practices, such as rituals, art, or meditations.

References

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis. Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988.