Exploring Place: Mapping to Connect

Maps visualize our place in the world, distill disparate facts into a single image, inspire adventures to new cafes or mysterious spots in the hills, and allow us to make sense of our home at a big-picture level.

On my family’s first trip to Ireland, my father had the misfortune of being both driver and navigator. My mom is directionally challenged; my brother’s only experience with maps was using them to find bosses in Everquest; and I was 12 and clueless. The duty of figuring out where in the world we were in a foreign country fell squarely on my father’s shoulders, and as if that wasn’t challenging enough, he had to drive on the wrong side of the road and was without a map. Like water or electricity, maps are one of those things that I never think about until the day I need and am without one. This was a week of that.

My family and I were trying to make our way to Donegal Castle from Dublin. It seemed easy enough on paper. The hotel clerk wrote directions on a notepad, and in our haste, we concluded his simple instructions were clear enough. He also told us as much. “It’s straightforward - just basically go straight,” he reassured us. Perhaps for a native, but not as a bunch of anxious yanks who thought Killashandra was a rapper and Boyle was something best lanced. It also didn’t help that we assumed the car carried a map of some sort of the Emerald Isle. Wrong. It only had maps of Dublin, as we were soon to discover.

Entranced by the rolling hills, the patchwork of hedges, and the villages nestled between, the countryside blurred into a stream of postcard-perfect film. While we enjoyed the sights, my father fretted over every turn-off and junction. His fears were justified. We had missed a turn an hour back. Fortunately, a friendly pub owner offered us the wrong directions, which wasted another hour. A trip of a few hours turned into a half-day, made all the worse by me and my brother complaining about how “we’ve been in this car forever already!” and asking “are we there yet?” ad nauseum.

When we finally did arrive, our spirits were crushed. A “straightforward” trip turned into a day-long disaster. My dad battled with a torrent of rage. My mother fantasized about how she might bring up with pops her plan to murder my brother and I, dispose of our bodies, and fabricate a cover story (or so I imagined in jest). My brother and I were miserable, starving, and bored out of our minds. I don’t know if we would’ve survived another hour together. I do know that we would’ve killed for a map to spare us our misery. We were in good company.

Since their advent in antiquity, maps have been prized possessions. During the Tudor period, spies risked their lives to canvas the European countryside, coast, and cities to gather intelligence. Their maps showed defensive positions, important geographic features, and other information that could be used in sabotage, politics, or war. If caught, such intruders faced torture and death, yet it was well worth the cost to the kingdom. Many battles have been lost because a general didn’t know that the flank they were charging into was a swamp or from miscalculating how quickly reinforcements could arrive.

During the Age of Exploration, European powers guarded their maps with the same vigilance as other national treasures. Maps and navigational charts were considered state secrets. The Royal Navy and trading companies like the East India Company tightly controlled access to these materials, forcing navigators and cartographers to swear oaths of secrecy under pain of death. Sensitive maps held on ships were designed to thwart rivals if captured. Some maps included intentional inaccuracies or omissions. Other maps were encrypted. Maps were their secret weapon.

Besides political and military intrigues, maps have been tools of governance. The Inclosure Acts led to the redrawing of the English landscape to formally divide common land into individual plots, which were documented in enclosure maps. The first Ordnance Survey of Ireland was completed from 1825 to 1846. Carried out by the Royal Engineers, the British produced a precise topographical map of the Irish countryside which would be used for land use planning, resource management, and war for decades to come. The survey also set the British back £860,000, or £100,000,000 in 2018.

Maps order chaos and confer power. The Tudors used their maps to navigate delicate geopolitical contests. The remapping from the Inclosure Acts allowed the upper class to legally remove unproductive small-holding farmers, expanding their domain while boosting national output. The Irish Survey greased the administrative wheels for tighter control of regions beyond the pale, a move which would eventually draw the Irish into a series of rebellions as the regime’s noose tightened. We use them today to find restaurants or travel to another province.

Most maps, like those above, concern themselves with political, military, and economic affairs, but they can serve other ends. Early Medieval maps, like the Gough Map, included religious landmarks and have provided insight into long-lost pilgrimage trails in England. Other pilgrim maps, like the Lübeck Pilgrim Maps, included way stations, monasteries, and other holy sites of interest on the way to Santiago de Compostela. Today, we use maps when finding a new restaurant or traveling to another province.

While it’s easy to dismiss maps as mere instruments of convenience, as history has shown, they are far more powerful than that. Maps visualize our place in the world, distill disparate facts into a single image, inspire adventures to new cafes or mysterious spots in the hills, and allow us to make sense of our home at a big-picture level.

The following mapping practices continue the spirit of exploration that drove the first Greek sailors to craft maps thousands of years ago. We’ll look at three different types of maps related to the land: 1) topographic, 2) creatures, and 3) buildings and infrastructure. Some of these you can find readily online, and others you must craft yourself. But like with the adventurers who came before, they help us visualize and order our place in a fragmented and vast world.

Topographic Maps

A place’s most fundamental aspects are its topography, climate, and geology. Without these, life would be impossible, yet they're so ubiquitous that most of us overlook them. Examining these features offers insight into the character of our land, the creatures that dwell there, the weather patterns that dictate life, and even local political antagonisms.

A discovery from a few years back shows just how fruitful map exploration can be. When the rainy season arrives, hundreds of streams vein across the plains and valleys of my Thai home. These streams start as gullies before swelling to torrents that continue to flow into the dry season, at which point they either wither up or settle into ponds until the rains return again.

When I first arrived, I looked to Google Maps to trace the course of these rivers, but they were nowhere to be found. I shrugged my shoulders and forgot about it, being busy studying Indian history and working my two demanding jobs. A few years later, I was puzzled again by the rivers and decided I was going to crack this puzzle. I opened a topographical map and studied the lay of the land. Due to the mountainous nature of the land, it’s difficult to make sense of the waterways and level changes. Diligence rewarded me with an insight; amidst the noise of the landscape, I noticed a downward slope from a mountain range 20 kilometers away. I realized that this must be where all this water was coming from.

The following rainy season, I tested my hypothesis. I biked along a river's banks until I reached the foot of the mountains. There, I discovered hundreds of streams running down the mountainside and gathering into rivers at its base. The waters rushed across stones, crashed down boulders, and poured back into itself. I was no Magellan, but I felt the exhilaration of discovery rush through me. A mystery that I spent years wondering over was solved.

I thought back to a Cold Mountain poem:

Born thirty years ago

I've traveled countless miles

along rivers where the green rushes swayed

to the frontier where the red dust swirled

I've made elixirs and tried to become immortal

I've read the classics and written odes

and now I've retired to Cold Mountain

to lie in a stream and wash out my ears¹

I had read many books on the migrations of the early Mon people in Thailand, biographies and analyses of the 10th-century Kashmir sage Abhinavagupta, and a geology textbook, yet I remained ignorant of the river that I biked past daily and the mountains, colored purple with the haze of distance, that ran along the horizon. Standing there listening to the hymn of these streams, I realized I'd ignored the majesty of what was in my own backyard.

The study of maps offers such revelations. This realization turned the hills and rivers from beautiful wallpaper to a friend who’s story I knew - not in full, for all life is wrapped in mystery, but enough to feel that a threshold had been crossed and a new relationship begun. It was one small piece of the puzzle that is my home, but it was an accomplishment nevertheless.

How To

This work starts with having the right maps. Get yourself maps of your area that focus on its natural features, such as its topography, geology, and climate. Given how quickly the technical landscape is changing, I listed recommended resources in the notes because in 5 or 10 years, those businesses will likely be replaced by better products.

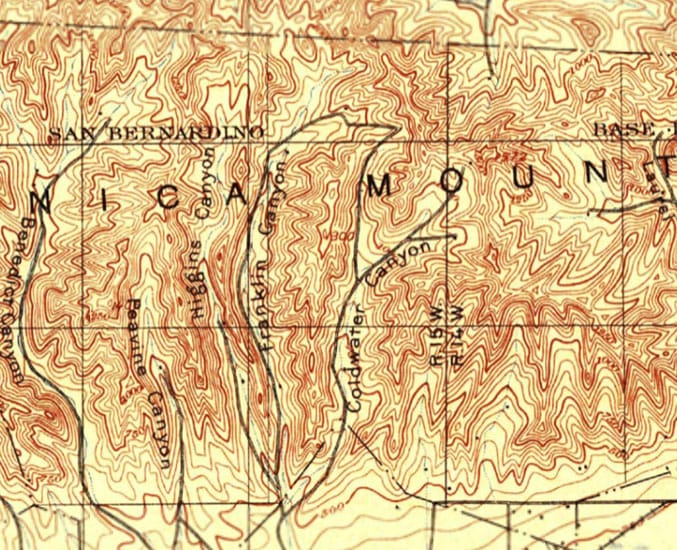

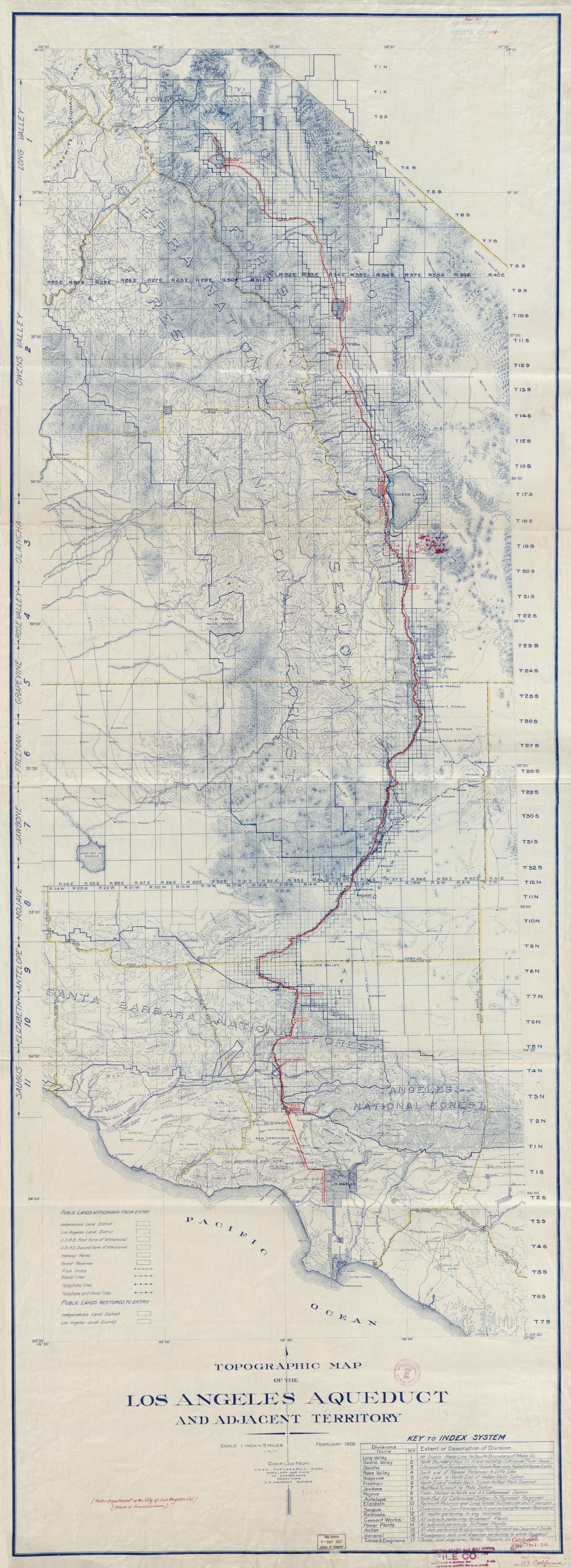

I also suggest you pick up some archival maps, particularly if you live in a built-up area. Seeing what a place looked like before ground was flattened, swamps drained, rivers diverted, and roads were lain can reveal much about the state of things now while connecting you to your land's history. These antiques are also sobering reminders of how quickly urban sprawl or a dedicated group of farmers can take over and subjugate a landscape.

As an example, compare my 1900s map of Franklin Canyon to the modern one before. It's astonishing to see how sparsely populated this area was just a century ago. No Beverly Hills. No reservoir. No Coldwater Canyon Drive. All that existed then was the Santa Monica Mountains and a few roads following the contours of valleys.

Once you've got your maps, pour over them and see what's of interest. Match your memories to the features displayed. Visualize how a place felt or looked at different times of the day or year. Notice any areas you’ve overlooked and plan to navigate those forgotten quarters. Compare different maps to one another. See how areas connect. Allow an organic whole to emerge from the disparate facts.

For a crafty project, print out a few simplified 5km² terrain maps. Select and label some of the highlights, such as:

- Spectacular Rocks

- Peaks and Valleys

- Ponds, Lakes, and Rivers

- Rare Mineral Deposits

- Cool/Hot Areas

- Viewpoints

If you’d like to take it a step further, give these places unique names. Many cultures worldwide, Celtic included, believed that names give their holders power. They’re absolutely right. Naming something, be it an emotion from drama at work or a shrub in a forest, plucks it from the haze of consciousness and pulls it into the light of the known. With that simple act, a whole host of characteristics and theories can be made of it. Consider for a moment the difference between a “tree” and an “oak.” A tree lives in a world of vague possibilities. It could be a 30-meter giant deep in the woods, but it could also be a scraggly hawthorn clinging to rocky earth. An oak, on the other hand, calls to mind a clear picture: rough bark, a sturdy trunk, the sheen of its leaves.

Take that a step further. Instead of recalling an “oak,” imagine Thor’s Oak. We’ve never seen it in person, but it’s easy to imagine a majestic giant set amidst a sacred grove. We would also recall that it’s not just a beautiful tree but also the sacred tree of Germanic pagans that was felled by Saint Boniface and used to make a church on the site. From tree to oak to Thor’s Oak, the object in question grows sharper, more concrete, more real, more alive with each subset. The pagans weren’t outraged and the Christians jubilant because “an oak” was felled. They reacted that way because it was Thor’s Oak. Likewise, no one ever falls in love with a “human” or a “woman.” We fall in love with Erin, Cassandra, or Sarah.

If you wish to fall in love with your land, let it be peopled with Erins and Shannons rather than rocks and rivers. This is how it was in the old days in spirit if not in form. The Shannon was not the Shannon River. It was Shannon, a river. The hills outside Tralee had names that hummed on the lips rather than being a nameless wallpaper for so many today. South and Southeast Asia keep this tradition of naming the land alive, with the Ganges River affectionately called Mother Ganga. Likewise in Thailand, every river is a mother. The Mae Khong River is called Mother Khong in Thai. The Mae Kwae River, where the notorious Japanese WWII railroad of death crossed before making its way into Burma and which was immortalized in the 1953 film The Bridge Over the River Kwai, is also simply the Mother Kwae.

Transform your landscape through the magic of names. Instead of a hill being “that one behind the grocery store,” call it “Lightning Peak” after all of the lightning strikes it endures. Let the valley between two counties be called “Bedb’s Cleft.” Call an unnamed rivulet “The Mossy Dreamer.” Names acknowledge the character that these features possess and turn them from faceless abstractions into companions of our fleeting world.

For another final tip when surveying, take a broader look at your homeland. Focusing on the crow’s range is extremely valuable, given the tendency of modern man to neglect the small and local, but the big picture is valuable too. Look at the area from a county, state, national, and international level. Follow the contours of mountains across state and national lines. See where a river springs from and ends. Notice the edges of a valley and the breadth of a plateau. Zoom back in and out, across and around. See how it all connects and where it fragments. This vision underscores that while the local remains supreme, it is always embedded within the seamless vastness of creation.

Creatures Map

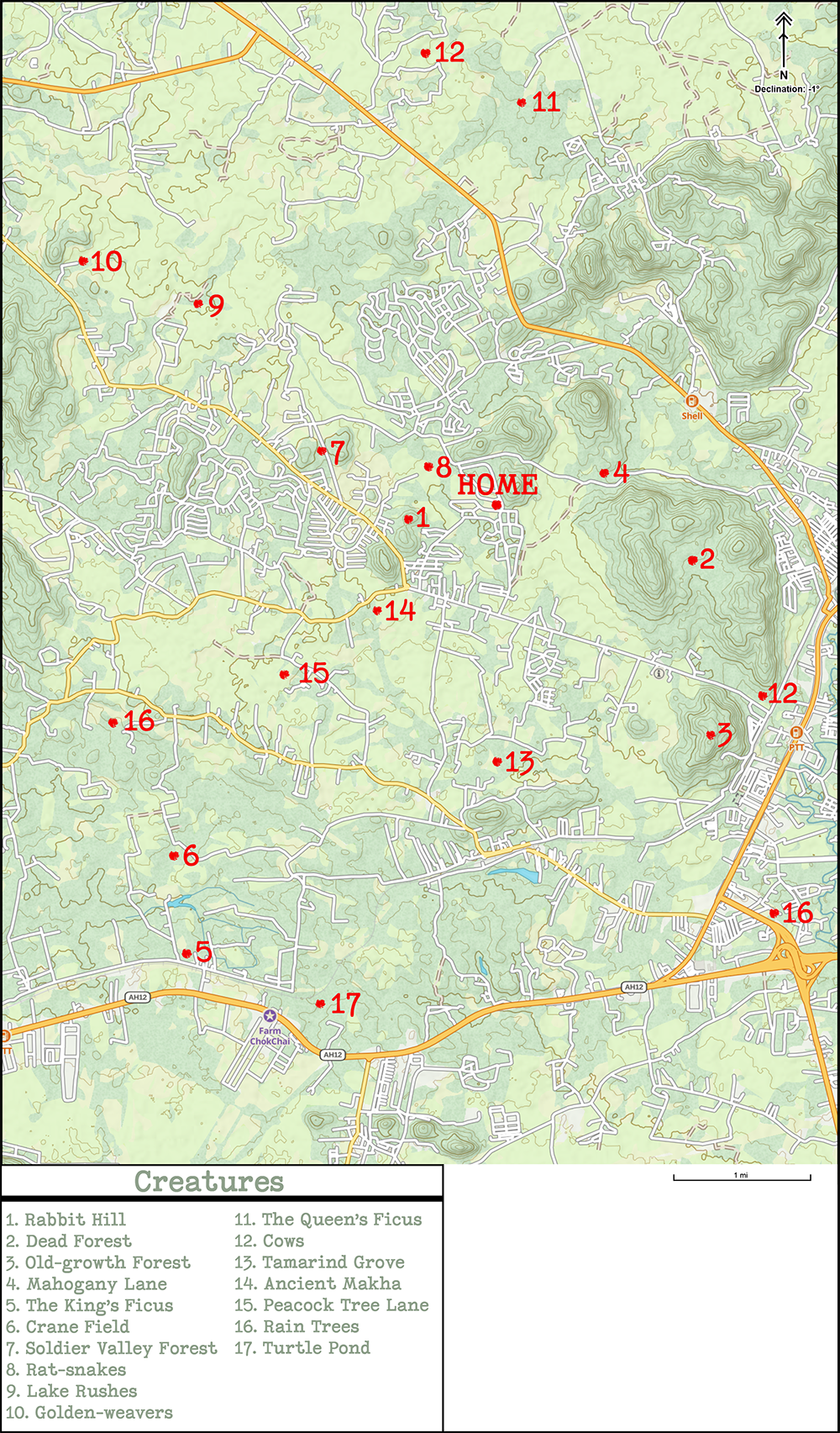

We cannot buy a map that tells us that a family of foxes lives beside the bridge nearby, that there's a white-tipped eagle's nest on the cliffs overlooking the Rory’s Cafe, that a forest a kilometer north of town is the best place for firefly viewing come summer, but for Celtic pagans longing to reconnect with nature, this information is far more valuable than knowing where the nearest Starbucks is. The creature map records these details, telling readers where the giant oaks worthy of reverence stand and where a new owl nest has popped up.

Since such maps can’t be found online or in stores, we must make them ourselves. No, it won't require a state-of-the-art drone and a Global Navigation Satellite System. All it takes is observing what's around, a printed (or digital) map, a pen, and an explorer’s spirit.

How To

Making these types of maps can take many forms, but for starters, I suggest you start with a few A3 printouts of roughly 9km×13km topographical view centered on your home. Digital maps are fine as well, but the tactile and demanding nature of physical maps makes drafting them more satisfying.

For the first draft, begin by recording landmarks by marking the spot with a dot/symbol and number. In the legend, describe each item. Some items you record could include:

- The Giants: ancient, large, or unusual trees that deserve special reverence.

- The Nests: the location of bird nests, fox dens, and snake lairs.

- The Hangouts: where and when do the kingfishers flock to the nearby lake or where you frequently spot deer ranging about.

- The Blossoms: where to spot gorgeous flowers at different times of year; feel free to include gardens here as well.

- The Misc: a forest meadow, a massive termite mound, and whatever else you find worthy of note.

As you mark up your map, you might notice pockets of intense knowledge and seas of blank spaces. Perhaps those places are barren or uninteresting, but perhaps they’re simply under-explored and appreciated. Make it a point to explore new frontiers and add to your map the characters that constitute your local land. Nature is everywhere; even the Death Valley is full of a life that escapes hasty observation. That area that you dismissed as empty might be full of unusual life that you’ve yet to spot.

Nature rewards patience. Some of her most extraordinary displays appear for but a few weeks every year, like the coming of orange-tip butterflies in April, the flowering of bee orchids, or the fruiting of golden chanterelle. Other spectacles are as unpredictable as they are fleeting, like a young fox marauding the neighborhood for a few weeks before moving elsewhere or a hen harrier ranging over the hills before vanishing, never to be seen again. Whatever you record, the map will reveal how ephemeral the world of the living is.

Another powerful practice already mentioned is to name the important features throughout your land. Rather than calling an oak “that giant oak in the park” call it “El Cid” after the legendary Medieval knight. Name a group of rowans nearby “The Daughters of Fand” for their reddish fall leaves and red berries in winter. Call a murder of crows “The Morrigan Gang.” Name your mother’s favorite meadow after her. Even if only you call them by that name, at least they can number you as one among their friends.

Buildings and Infrastructure Map

The final aspect of the land is its buildings and infrastructure. It amuses my friends when I say this, but I'm frequently struck with awe and gratitude for the infrastructure we've created. Two human inventions that have made life inestimably easier and safer are plumbing and asphalt roads. I've lived in places where water’s drawn from distant wells and where the roads were dirt tracks through the jungle.

It sounds nice on paper, but the reality is not so enchanting. Without running water, cleaning is next to impossible. Showers consist of plunging into a nearby river (when there’s sufficient water). Cloth washing requires spending hours scrubbing them down by the river. And you can kiss changing t-shirts everyday goodbye. You’re going to be wearing that dirty shirt for a while, so enjoy. Roads are another underappreciated area in the developed world. Locals love to complain about potholes and faded traffic lines, but that’s nothing compared to having rutted dirt roads that have become nearly impossible to traverse. Worse, when storms come, those roads become impassable, and getting from place to place begins and ends with you calf-deep in mud and leeches. Good luck if you have an emergency and need to get to a hospital. Despite its ills, civilization has its wonders.

How To

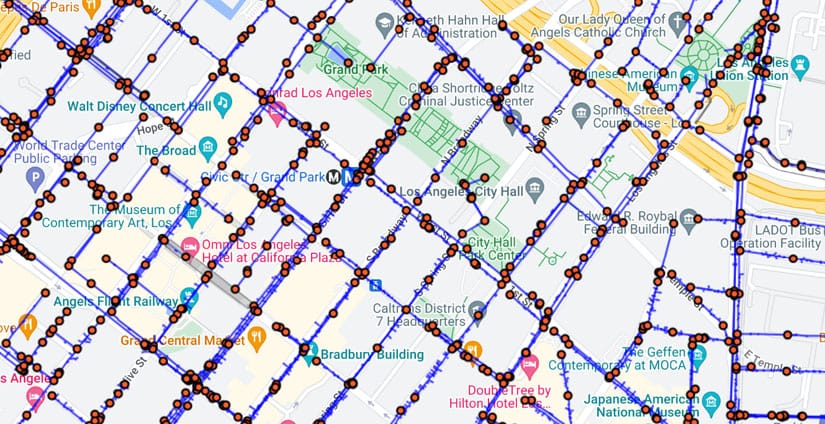

Since maps for buildings and infrastructure are plentiful, I won't list where to find such things. What I will mention, however, are some unlikely topics for you to look into. One place to start: your toilet and wall sockets. Find your local city's maps of water, electricity, and sewage. A glance at these maps shows how much work has gone into water streaming from the tap at a nob’s turn or a flush of the toilet. In many remote communities, villagers must carry water to their homes from a river, and bathrooms are pits in the ground. Compare that life to Los Angeles, where 17,000 miles of publicly owned pipes save residents from having to carry water home each day.

If LA residents look at where the water in those pipes comes from, they'll discover 674km of aqueducts running from the Colorado River and the Sierra Mountains to their kitchen sink. Water doesn't magically flow from their faucets, sourced from the ether’s fecundity. That water's brought there by over a century of engineering work and the abundance of nature. It is a gift - and one which would implode the city if it ever stopped giving.

Taking these things for granted is easy, and boring old infrastructure maps correct that. The black line below is the vein that keeps life in Los Angeles pumping. Our cities, with their cell-like homes and filaments of electricity and water, mirror our own bodies. The visual is a reminder that this city, too, lives, that this city, too, is one with nature's weft.

On the building side, look for buildings of particular beauty, history, or utility. Make special note of the quiet government properties that keep things running. The sewage plant. Post office. Department of Water and Power. Shipping docks. Like water, air, or soil, humans are too good at forgetting the fundamental for the shiny new thing over there. Returning back to the primary requires frequent reminders before it's instilled within, before our eyes see the landscape as one seamless, living whole.

Map Resources

- GaiaGPS has a wide selection of digital maps, including natural, geological, and historical maps. Even its free version blows Google Maps out of the water. It has a crisp and intuitive UI and a wide selection of layers and is nature-focused. If you want all the bells and whistles, you have to pay a monthly subscription, but the free version is also good. Unless you're a map addict, you can pay for the monthly subscription once, download the maps you need, and then unsubscribe.

- FATMAP is a 3D satellite map. It lacks many features but makes up for it with its unique ability to go down valleys and up mountains in 3D. On 2D maps, you must estimate a mountain’s height or an incline's steepness using lines or numbers. For non-professional surveyors, translating those figures into terrain is difficult. Viewers can immediately grasp those spatial differences when placed on a 3D map. FATMAP offers a free and paid version.

- Omnimap lives up to its name and offers almost every map imaginable, ranging from seismic activity to natural resources. The downside is that they only sell physical copies, and the website is stuck in the 90s. But if you're looking for big, high-quality print maps, this is the place to go.

- USGS Topo contains many detailed digital maps of the US, including archived maps, for free. The UI is clunky and designed for professionals, but there's still value to be had from it. For those not in the US, most other countries have similar services available.

Notes

- Han Shan. The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain, trans. Bill Porter (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2000), 125.