Is posture important?

How important is posture in meditation?

What posture’s easiest to sleep in: lying, sitting, standing, walking, or running?

Lying, duh.

And what do you do if you’ve been working for a few hours and are starting to feel yourself dragging? How would you freshen yourself up? Doomscroll through Twitter?

Sometimes, yes. Doesn’t help, though. On my lunch break, I sometimes go for a walk around my office to get the blood going and unwind. After work, I’ll lift or run.

And what if you want to have utmost concentration while working?

Sit down in a quiet room with notifications off.

Your answers are right there.

Yes, posture’s important, but in Zen they make a big stink about it. When I went to the San Francisco Zen Center for an intro course on meditation, they spent most of the time going on-and-on about the posture. Sit perfectly straight, not slumping forward, not leaning backwards, not cocking your head one way or another. Hold your hands exactly three finger breadths down from your belly button. Right hand over the left. Then they went and checked everyone’s posture. I sat there with my chest puffed out and a cocky smile on my face, certain that I sat as perfect as the Buddha. I was wrong. The teacher came over and pushed my back in, cocked my head, tucked my chin in, pushed my elbows out and up. My ego deflated instantly and, not only that, sitting “properly” felt so wrong. “Am I really this out of touch with my own body?” I wondered. My elbows shook under the strain of aligning with my hands. My back ached. My neck yearned to return to its crookedness.

When I returned to my dorm that afternoon, I sat in front of the mirror, closed my eyes, and settled into what felt like a correct posture. I was horrified when I opened my eyes. My head torqued to the left. I leaned hard to the right. My mudra was crooked. I straightened everything out, closed my eyes, and counted the breath. A few minutes later, I opened my eyes to asymmetry again. That afternoon sparked years of obsession.

I started practicing yoga because, in large part, I wanted to sit in full-lotus and get my meditation turbo-boosted. I made it a habit of sitting in front of a mirror and nitpicking over my symmetry. I spent months figuring out the perfect position to rest my eyes, only to decide it was all wrong and move it a few inches further up or down. Eventually, I could sit symmetrically in full-lotus, but my mind was still a mess. You’d think that I would’ve realized how preposterous the perfect posture shtick was, but no. “Any day, now, my perfect posture was going to catapult me to enlightenment,” I reassured myself.

It wasn’t until I did my first Burmese meditation retreat that I realized how silly the Zen posture obsession was. My teacher, a renowned doctor and meditation master, was fat, messy, and hunched over. The exact opposite of the lean, clean-shaven, and upright Zen monks that I had come to equate with enlightenment. But in his presence and under his supervision, I realized that enlightenment can also look like a crookbacked grandpa.

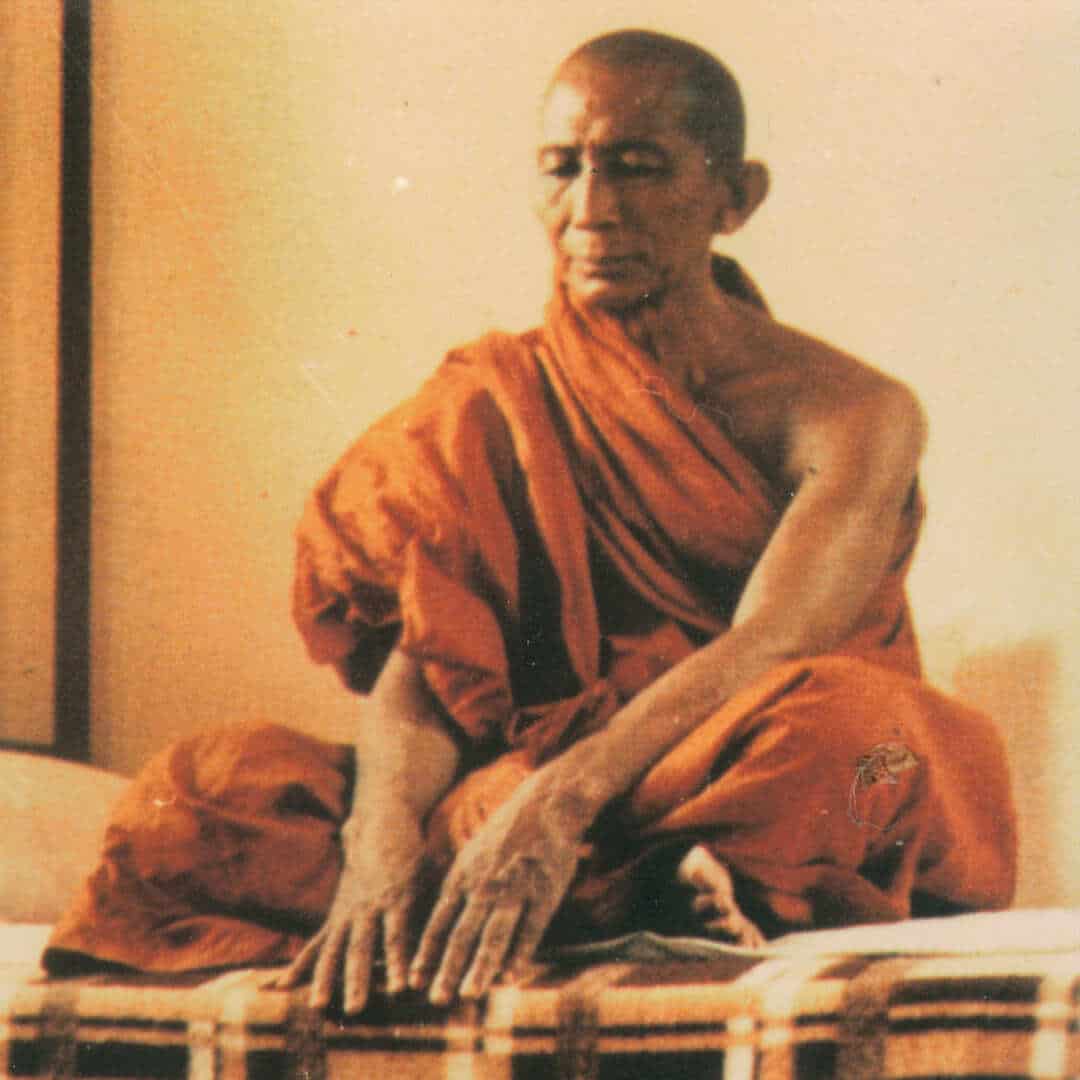

While under his tutelage, I became acquainted with the Burmese Theravadan tradition and their masters, many of whom spent much of their lives devoted to meditation. Above is an image of one of them, Webu Sayadaw, a meditation master of the 20th century. How you see him photographed is how he often sat, Indian-style, slightly hunched over, his hands touching the floor.

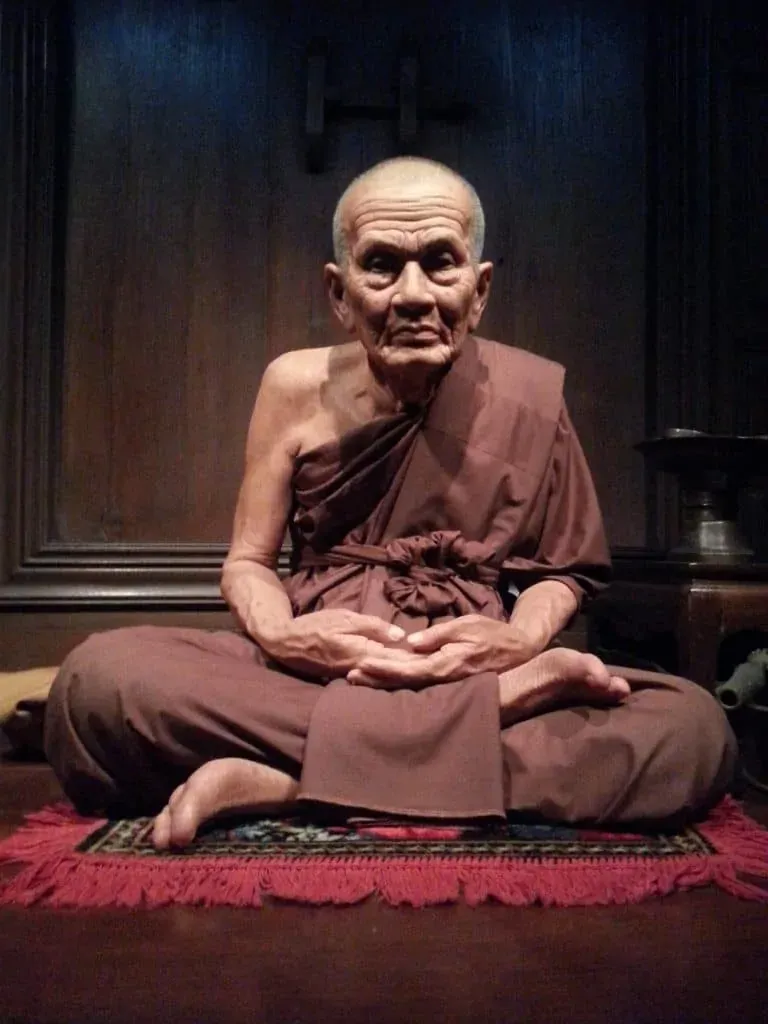

When I traveled to Thailand and ordained in the Thai tradition, I saw that the Burmese wasn’t the only tradition with hunched masters. Above is a statue of the mythical Luang Phor Tuat. Separating fact from fiction is dicey business, but the meditative posture portrayed is one that I’ve seen countless times by living meditation masters in Thailand. Hunched over, hands resting on their lap. Legs folded casually atop one another. It’s a simple, natural pose that works.

But isn’t this Theravada, not Zen?

Yes, but truth is truth. The point is that having a good posture’s not that important, a fact evinced by the slumped backs of these masters. I still don’t want to look like Luang Phor Tuat when I’m 70. I still try to sit upright and symmetrically, but I don’t fuss much about it. The most important thing is that the Five Factors are continuously developed. With those, your meditation will fly even if you slump. Without them, your meditation will flounder even sat upright.

What is important is the right posture, not perfect posture.

What’s the difference?

The right posture means when you need high levels of focus, you sit. When you need to relax and unwind, you lay down. When you need to recharge and freshen up, you walk. You choose the proper posture, but you don’t obsess over lying, sitting, or walking perfectly.

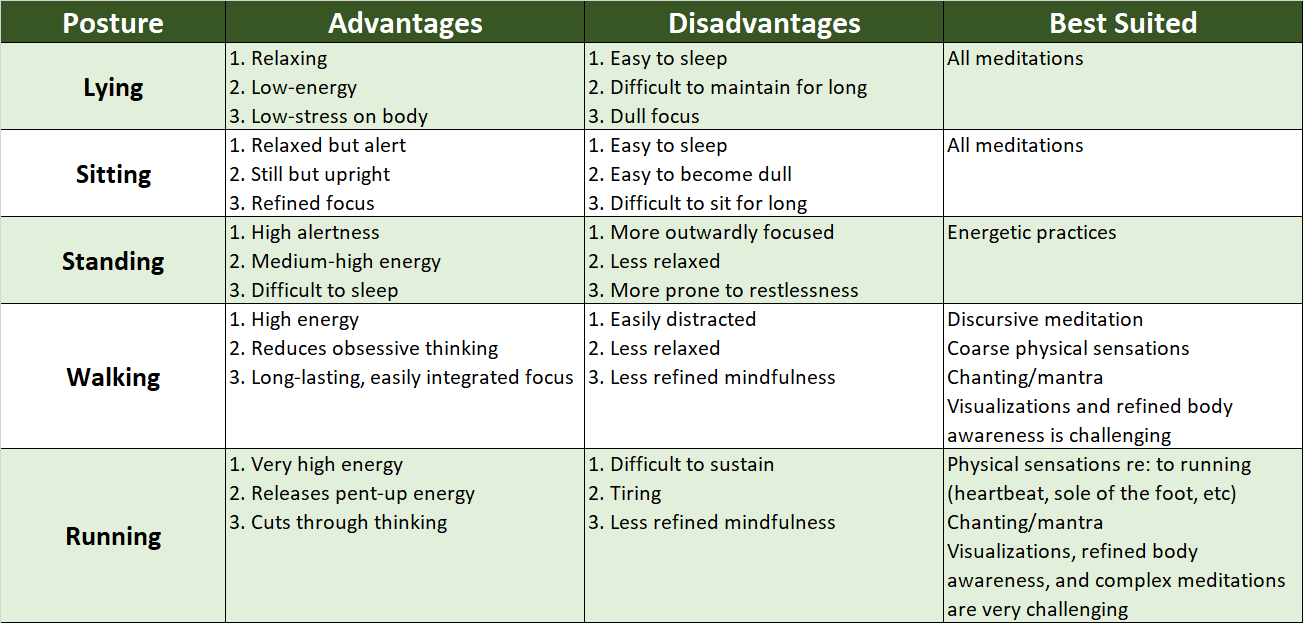

To understand the right posture for the right situation, Zen traditionally divides the postures into four categories: lying, sitting, standing, and walking. I’ve added a fifth: running. Each of these five postures are suitable for different situations. For beginners, knowing just sitting and standing is usually sufficient, but as you grow more skilled at working with your mind, you’ll find the other postures useful to draw on from time-to-time.

Posture 1: Lying

Lying down is good for when you need to rest body and/or mind. If you’re super restless or your head’s buzzing with activity, lying down often calms things down. When meditators get back from an intense day at work, they often default to distraction to unwind. Turn on a beloved anime, their favorite action series, a podcast, whatever. Instead of going for distraction, they can just lay down and rest the mind with the breath. This can bring quick relief and leave them sharp and ready for the night. For physical exhaustion this is also the go-to posture.

Lying does, however, come with three big drawbacks: 1) it’s easy to fall asleep, 2) difficult to maintain mindfulness for extended periods, and 3) mindfulness tends to be dull.

There are a two classical lying poses:

1. The Lion’s Pose

If you see a statue of the Buddha laying down, he’s in this pose, referenced throughout Buddhist scripture as the Lion’s Pose. For this pose, lay on your right side and hold your head up with your right arm or propped up with a pillow. Extend your left hand and rest it along the length of your body. Rest your left leg atop your right. Settle in and meditate. You can also switch sides, however, laying on the right side is more energizing.

2. Corpse Pose

Lay on your back and place your hands, palms up, by your side. You can straighten out your legs completely and let them relax, although this might wear on the joints. You can reduce the strain by placing a pillow underneath your knees. Another variation is to cross your legs or raise them halfway, forming a v-shape with your knee at the peak. The advantage of raising your legs halfway is that your legs will collapse if you doze off and might startle you awake. Honestly, I sleep through it and many others do, but it does help for some.

Posture 2: Sitting

This is the king of meditative poses because it sits midway between relaxation and alertness, the two essential factors for meditation. Another reason is because you can remain still for long periods with little effort, discomfort, and distraction. But, as with all postures, there are disadvantages. Compared to standing or walking, it’s far easier for dullness to settle in or end-up nodding off. Sitting also puts strain on the knees and back, especially for the unflexible, and can quickly become unbearable after long stretches.

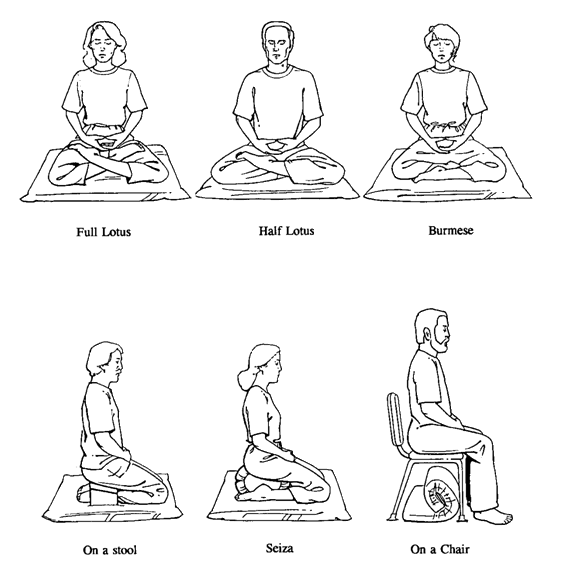

There are a couple of different ways to sit, pictured below:

Whatever pose you choose, once you sit down set your posture. Start by relaxing your shoulders. Then sway gently left and right a few times to find your center line. Next sway forwards and backwards to find the other center line. Once you’re aligned, extend your spine by feeling as if an invisible string was gently pulling you up from the crown of your head. For the mudra, you can place your hands in a number of different ways. The classic Zen mudra is the cosmic mudra, pictured above. Other mudras include placing your hands on your knees or gently clasping them together. While chanting, the hands are kept in anjali. Then keep the lightest touch of awareness on your posture to keep it in place.

After setting your pose, turn your attention to your meditation object. You might come back to it during the meditation to check how well you’re holding your posture and the state of your mind, but keep it to a minimum. Once or twice a sit’s a solid number, as it’s enough to correct for errors and check-in, but not so frequent that you end up focused on how you’re sitting rather than the meditation itself.

Posture 3: Standing

This is a rarely used but a very effective posture, especially for beginners or when doing energetic practices. For meditators who have low-energy or tend to doze-off, consider standing instead. The sheer act of forcing oneself to stay upright will keep the mind energized and sharp. Standing might seem like it requires little energy, but I think back to all the times I’ve gone to a museum and spent a few hours standing in front of Waterhouse’s or Turner’s paintings. By the end of it, I’m exhausted from all the standing. The strength of standing, however, is also it’s weakness. Since it’s so energy intensive, it’s less restful, requires more outward focus to maintain balance, and can exacerbate restlessness.

If you train in yoga or qi gong, they’ll have dozens of poses for you, but for starting out, there’s just one pose:

1. Open Pose

Keep your spine upright, like there’s a thread pulling up from the crown of your head. Relax your shoulders. Let your arms hang freely from your side. Keep your chest wide. Bend your knees slightly without leaning forward. The slight bend of the knees is to prevent your knees from taking too much pressure. You can combine this with various mudras, like prayer, cosmic, or tree mudra for more energy.

Posture 4: Walking

Walking meditation gets the blood flowing, boosts energy, and keeps the mind and body active. As such, it’s ideal for fidgety, restless, or drowsy meditators. The samadhi that you develop from walking meditation also lasts longer and carries over more easily to daily life. However, it’s easier to be distracted, more difficult to settle down, and difficult to maintain refined mindfulness.

There are two basic ways of walking meditation and one walking-esque variation.

1. Pacing

Walk back and forth at a natural pace between two fixed points or in a circle around. If you’re pacing for longer than 20 minutes or have sensitive joints, I suggest you walk at least 15 natural steps. Walking in confined spaces will wear at the joints after pivoting hundreds of times. As such, 15 paces and up is the standard used for walking meditation paths in Thailand. If you’re circling around, one lap should exceed 30 paces.

As you walk, keep your gaze soft and a few paces ahead of you. You may place your arms behind you, at your side, or in front. Do what feels comfortable. Stay with your meditation object with as few interruptions as possible. Note, however, that some practices will be very difficult while walking. For example, staying with the breath or visualizing will be very difficult. In Zen monasteries, as in Thailand, the standard practice for walking is chanting, mantra, or focusing on the sensation of walking.

2. Ambling

Go for a long walk. You can walk randomly with no particular destination in mind, but familiar paths are best so you can stay with your meditation object rather than gawking at the scenery. A long walk out in the sun, fresh air, and the sounds of the birds washing over you can recharge like no other. As with pacing, keep the gaze soft and focused on the ground. Keep your mind on your object.

3. Bowing

Bowing is also used as a meditative posture that’s mid-way between walking and standing throughout East Asia. It’s especially useful in colder climates, like Korea and Japan, where temperatures dip below freezing in the winter months, or when walking space is limited.

There are two main styles. In the Korean style, start in a stand with your hands in anjali then lower yourself down, press your forehead against the floor, and uplift your arms. Note that this video isn’t perfect, but it's the only one I could find. In the Tibetan style, you extend yourself full on the floor before picking yourself back up. You can perform bows with a mantra, with awareness of the movements of the body, or focusing on the breath.

Bowing is an effective way to get the blood flowing and tame an overly active mind without having to go outside. Because it’s such a complex motion, however, it’s difficult to integrate it with many other practices and it can wear on the joints, especially if done improperly and/or for extended periods.

Posture 5: Running

When I was training at Tofuku-ji, one of the storied Japanese monasteries, we did stints of walking meditation during the week-long retreats, but it wasn’t the the slow, drowsy type that most imagine. Instead, we half-jogged around the meditation hall in big strides. It was comical, at first, to see a bunch of bald pates and black robes racing down the walkways, but I came to savor those brief sessions. They super charged my energy and calmed my mind when it was besieged by restlessness. There are, though, some disadvantages. First, unless you’re training for a marathon, it’s unlikely you can get in long stretches without risking injury or tiring yourself out. Also, as with walking, it’s difficult to enter more refined concentrated states and slip into serenity. You can enter flow easily, but it’s very, very difficult to take concentration any deeper.

This covers the five main postures. It’s worth repeating here that if you’re just starting out, sitting and walking meditation’s sufficient for most beginning meditators, but as you gain more experience and skill, begin to play around with the postures and see how they affect meditation. What does it feel like to meditate on your koan while jogging? What does it feel like while lying down? What does it feel like standing? How do you deal with sleepiness when it overcomes you? What about when your fidgety and just gotta move but your schedule says: 15 minutes first thing in the morning? These are all opportunities to try them out and learn more strategies to manage and develop the mind.