What are the basic principles of meditation?

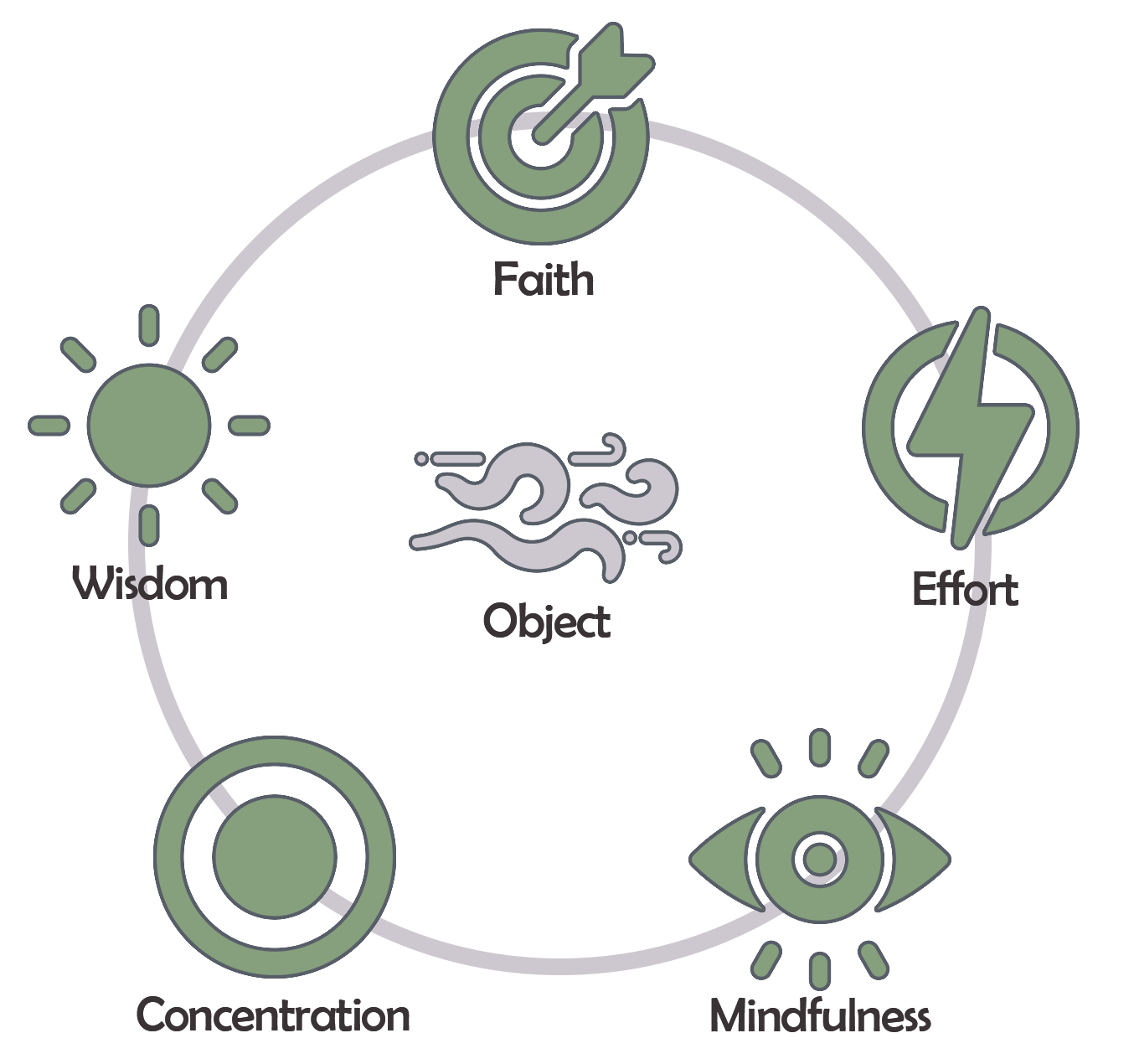

This time I’m starting because there’s an important question which I doubt you’ll ask about: what are the key factors of a successful meditation practice. Last time, we discussed the why, what, and how of meditation in broad strokes. However, we didn’t cover how with sufficient depth. Before explaining the specific practices, it’s worth reviewing the factors that can either make or break your meditation. Once you understand what they are and how to apply them, then you can meditate using any technique successfully. Those key factors are known as the Five Powers: faith, effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom.

That sounds like a lot to keep in mind.

It can seem like too much information, but if you want to learn any skill, be it painting, carpentry, or weight-training, you need to understand the basic theory to do it effectively and safely. Meditation is no different. Some beginning meditators come to Zen thinking they can just pick it up and succeed without any background knowledge. That DIY approach can work, but it also carries the risk of spending months or even years wasting time on mistakes that could’ve been avoided by consulting with the tradition and experts.

For brand new meditators, much of this will go over their head. That’s fine. As they practice, experience will fill-in the gaps. Also, when things go pear-shaped - and they will, meditators can return to these concepts and use them to assess the situation and find solutions.

In that spirit, I’ll cover the Five Powers one-by-one and include a list of specific practices to properly balance each one.

Faith

Faith here isn’t blind belief in a higher power, rather it’s confidence that what you’re doing works. If you start a new diet, for example, you must have faith that it it’ll help you lose weight before you begin. Initially, that faith is speculative. A good friend of yours trimmed down after a year on the paleo diet. A few well-researched books gave the thumbs-up. You’ve consulted your GP and he agrees that it’s worth a shot. Based on this information, you hope that it will work. Thus, you’re willing to endure all of the restrictions, learn new recipes, spend more money on specialty foods in the hope that this will help you meet your fitness goals. It’s the same in meditation.

Starting out, faith is the result of reasoned reflection. You’ve looked at the research on meditation’s benefits, you’ve seen how it changed the lives of your friends, and you know how calming playing the guitar is - which seems similar to meditation. Perhaps this will really help you so you read a few books on the subject and carve out 20 minutes a day to get at it.

After you’ve practiced for some time, though, you begin to see the results for yourself. You see that you’re more confident, composed, and powerful. You’ve used these techniques to manage your anger and anxiety countless times. You know that this stuff works and that confidence borne from experience and reflection is faith.

If you listen to some meditation teachers, though, you might hear some phrases like “practice without expectation” or “meditate without desiring results.” Nonsense. If you really had no expectation, would you sit down to meditate in the first place?

If I’m honest with myself, no. I want something from it, otherwise I’d be doing something else more worthy of my time.

Exactly. Telling would-be meditators to “expect nothing” puts them in a double-bind. First, it tells them that the healthy desire that drove them to seek out meditation in the first place is wrong. Second, it then places an impossible burden on them: to expect nothing. It’s bad advice.

But what about when, say, a friend goes out on a date and says that he’s not expecting anything. If it works, it works. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

Still rubbish. He wants something from the encounter, whether it’s to find a partner, get laid, or at least meet a new, interesting person. He’s not inviting the grandpa down the street for a date, is he? He’s not inviting any of the girls he swiped left on. He’s going out because he hopes something will happen. It would be clearear if he said, “There’s a chance that nothing comes of this, but it’s worth the risk.”

So what would you say to beginning meditators about expectations, then?

Expect! Expect great things. Expect out-of-this world bliss. Expect serenity for hours without end. Expect laser-like concentration. But also expect to wait a looooong time and put in the work before that potential becomes reality.

You don’t have to dream big. You can start with a modest goal of just being able to enjoy sitting quietly. The advantage of big dreams, though, is that they motivate more. The hope of attaining otherworldly bliss at the snap of your finger tips - a real possibility for a skilled meditator - is far more attractive than the thought of mildly enjoying sitting alone. A big dream like that also reminds you of what you’re capable of and not to settle for lesser fruits. For big dreams to work, though, you should set lesser goals and milestones to measure the way. One smaller goal might be to sit in peace for 30 minutes regularly. Another, to enter higher meditative states. Another, to just pull through a tough period with your sanity intact. Faith is knowing that those goals are within your grasp and gritting through difficulty to achieve them.

Faith, however, is a double-edged sword. Over expect and it can derail meditation. Perhaps you start meditating after reading books about legendary practitioners and you want that, so you sit down eager to follow in their footsteps. But instead of sinking into a profound stillness, you’re assailed by thoughts about how stupid you were for leaving the keys on the kitchen table last week and worrying about the upcoming deadline. You push harder, thinking you can just brute force your way to serenity, but you feel more restless. Before the timer rings, you give up, certain that there’s no hope for you. This is the turmoil of over expecting.

When Ajahn Chah got serious about his meditation practice years after ordaining, he was hungry for results. Wishing to push past his tepid meditation, he determined to sit all through the night without moving. He lit an incense stick, used in the old days to measure 30 minute sessions, set it out in front of him, and closed his eyes. He wrestled with his mind for what seemed like hours until, certain the incense stick had long been extinguished, he opened his eyes and glanced down. It wasn’t even half-way! “Not even half-way!” his mind screamed. He closed his eyes and white-knuckled it for another eternity. He glanced down again. There was still a quarter of the incense stick left. The sight deflated him completely. “There’s no hope,” he concluded, “for a monk like me.”

Later, reason came around. He realized that he needed to lighten things up if he wanted to progress, not make big vows and expect enlightenment in a night. Years of struggle laid ahead of him, but this was one small victory for him.

So how do I manage those expectations in meditation?

Start by frequently checking your attitude and feeling towards meditation. Do you really want to sit down today and meditate? Do you really even know why you’re doing this anymore? Because if you don’t know why and you don’t feel good about it, excuses will come. “It’s ok, sleep in today. Yesterday was rough.” “It’s not a big deal if you skip, it’s just one day.” “Things are going so well now, you deserve to sleep in.” The most worrying is when you don’t even make excuses to defend yourself.

Here are a few tips to develop faith:

- Check-in with yourself: Every few days, ask yourself, “How confident am I in my meditation? What do I expect from meditation? Why am I meditating?”

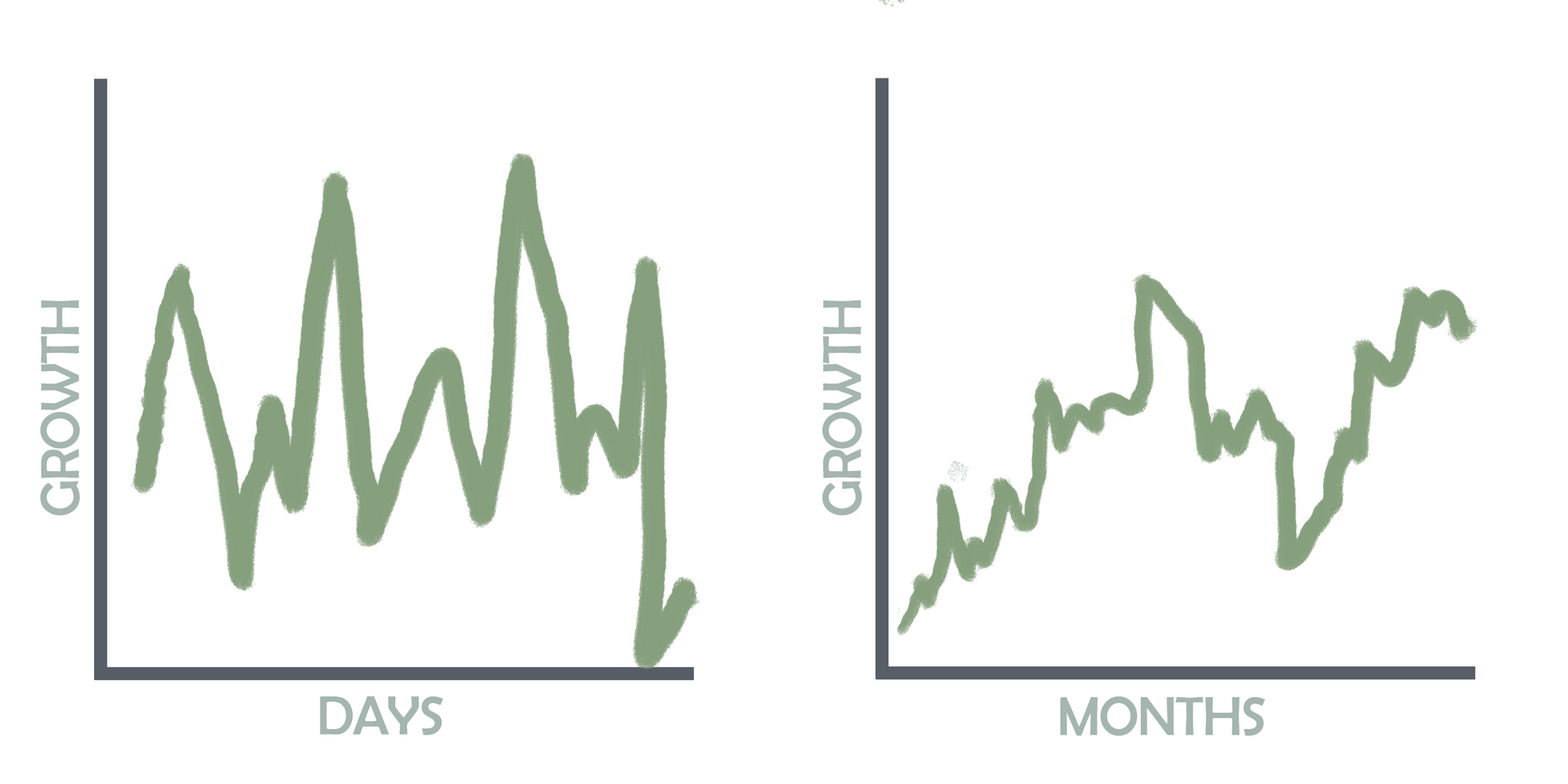

Reflect on your past and the purpose of meditation. Progress in meditation is messy. If you measure progress over a short time-scale (days/weeks), it's easy to feel like you're getting nowhere. If you step back and look at it over a longer time-scale (months/years), it's easy to stay motivated and grateful. Train yourself to focus on long-term trends rather than individual moments or short-term chaos, otherwise you’ll be trapped comparing your meditation now to an amazing session you had months ago or feeling depressed by the ups-and-downs of the mind. Also, think of why you came to this practice in the first place. It doesn’t have to be to achieve total-mastery of the mind or enlightenment. Maybe it’s just to be more aware throughout the day. Maybe it’s to buttress yourself against the forces of depression and anxiety. But keeping that goal in mind and pursuing it will muster more discipline and focus. - Befriend practitioners. One of the first things suggested to an addict trying to quit is to stop hanging out with friends that use. The opposite is also true: if you’re trying to strengthen a habit, hang out with friends who’re into it. You’ll have someone to share experiences with and keep you motivated.

Work with a teacher. A meditation teacher guides, motivates, and holds you accountable. I might be a bit biased, since I’m in the business of teaching this, but millennia of contemplative tradition backs me: having a teacher’s the most important factor in spiritual growth, including meditation. Having an experienced guide reduces doubt and is a well-spring of motivation. - Set small goals. Expectations are good, however, they don’t motivate very well when they’re vague or too far off into the future. Set SMART goals to keep yourself motivated. The goal can be as small as meditating for 10 minutes a day, but I suggest you make result-oriented goals, like being able to go 100 breaths without losing count or 8/10 sits being focused. If you focus on simply clocking time in, that’s not going to motivate you. Imagine if your boss at work told you, “Our goal for our upcoming project is for everyone to work for 2-hours a day on it.” You’d probably roll your eyes at how silly it is. Time should be the metric used to ensure that the team paces itself to reach the goal, not the goal itself. Meditation is the same. 20 minutes a day isn’t going to push you to excel, it’s going to encourage you to treat it like a job where you clock-in and clock-out. Don’t bring that kind of energy. Bring a “hell yea, I can do this” attitude every time.

Regarding setting concrete goals, defining those goals as a beginning meditator will be difficult. Begin by just getting experience and developing a habit, but once you become more familiar with the inner territory, start defining the goal in terms of the quantity and quality of the meditation rather than quantity alone. - Witnessing thoughts. This is the go-to meditation for when doubt starts to wreak havoc within. I’ll detail how to do it later, but if you’re feeling besieged by uncertainty, you can always take a time out from whatever practice you’re doing and deal with the doubt head-on. If it’s so bad that you switch objects, though, I suggest you take a break from the main practice altogether for a few days or a week and just witness thoughts. Once it’s under control, come back to your main meditation object with a fresh mind.

That’s so much stuff!

Yes, but it’ll come in handy when you’re struggling with faith and don’t know how to fix it.

Got it.

Effort

The classical metaphor for effort is of a lyre player tuning their instrument. The strings should neither be too taught, nor too tight. Try too hard and restlessness and burn-out are in the offing. Try too little and it’s sleep or a long list of excuses. But where just right is for each person depends on where they’re at. For the Buddha at the end of his path, just right looked like this:

Gladly would I let the flesh & blood in my body dry up, leaving just the skin, tendons, & bones, but if I have not attained what can be reached through human firmness [enlightenment], human persistence, human striving, there will be no relaxing my persistence.'*1

That level of determination was just right for him then, but that’d kill me and most practitioners. For a beginner crawling their way out from a life of indulgence and distraction, just right might sound more like, “Ok, I’m just gonna do 5 minutes today and take it easy.”

And how do I find what’s just right?

How do you know when the string’s out of tune? You have to develop an ear for it and that comes through practice. A lot of practice. However, Mingyur Rinpoche, a Tibetan meditation master, has a nice metaphor for finding that sense of just right in meditation. He said that meditation should be like having coffee with an old friend. You should look forward to it, even though there are tinges of anxiety or the pull to just stay comfy at home. While you’re having coffee, enjoy yourself and focus on the conversation. Don’t check your phone. Don’t check-out the barista. Once the conversation naturally winds down, you know it’s time to go your separate ways. Meditation should be the same way.

You should go into most meditation sessions with some enthusiasm. During, it should feel nice. Sometimes, though, it will be tumultuous and uncomfortable. That’s fine, just so long as it isn’t every time. 1 rough meditation sessions in 5 is a solid ratio. Anything much higher than that will become a chore. Finally, you shouldn’t push it too long. When it feels like it’s dragging, it’s time to wrap things up.

Joy’s essential for the mind to settle into stillness. Dragging yourself to meditate or white-knuckling it to make it to an hour doesn’t work because it sucks all the joy out of it. In the long-run, forcing yourself to meditate like this will build up resentment and make the mind restless. Eventually, the mind will make a thousand excuses and think of a thousand more important things to do rather than meditate. The resentment and dissatisfaction can also express itself by rejecting the teacher or technique. “I can’t meditate on the breath because it’s too hard. There are more effective ways out there. Why am I wasting my time on this?” Or “This teacher’s horrible. I’ve made no progress with this clown!” Those criticisms might be valid, but if you’re forcing yourself to meditate and endure 45 minutes of discomfort for months on end, those complaints are likely your heart screaming, “STOP DOING THIS! I’M SO TIRED OF THIS GARBAGE!” Pull off the gas. Do less, enjoy more.

Right effort is enjoying meditation from beginning, middle, and end. There will be days where you have to drag yourself to meditate and your mind’s a complete mess. Accept it and exercise your will to do what’s good for you. However, if you’re doing that regularly, it’s time you change your routine. It could very well be that 5 minutes a day is the right amount. If even that’s a challenge, try other activities instead, like music or sketching. What you enjoy will sustain you and sustain itself.

The other aspect of right effort is how you apply the mind while meditating. The two principles my teacher, Ajahn Sudhiro, taught me and that have held up time-and-again are to keep the practice simple and natural.

- Simple: One of the first things meditators do when they’re pushing too hard is make the practice more complicated than it has to be. Don’t. If you’re counting the breath, no need to count according to the Fibonacci Sequence or sums of isosceles triangles. Count from 1-10. It might seem like you’re getting ahead, but complication leads to a sense of busyness, stress, and being too self-conscious. These feelings undermine focus and joy.

Also, don’t try to hack concentration. Meditation isn’t a video game where you can bug-out and jump to level 10. If there were hacks, teachers would eagerly pass them on to future generations, but there aren’t. As with lifting weights, there are methods of differing effectiveness, but nothing’s gonna get you ripped in a week. Keep it simple stupid. - Natural: The other common symptom of overexertion is gripping the object. For example, when trying to follow the breath, overzealous beginners focus very intensely on the breath. This might offer a brief boost in concentration, but it will be brittle and unstable in the long-run. Eventually, your mind will collapse under the pressure and you’ll be worse off. Instead, naturally be aware the breath. What is naturally being aware? It’s what happens when you sit down to study for a test, try to header a football, or parallel park. That’s it. Keep it simple stupid. There’s no need to overthink this or try to find some workarounds. Meditate like you park your car. You don’t try to stop thoughts. You don’t try to stop sounds or sensations. You ignore them and keep your attention trained on the object. If it drifts, bring it back.

Do you have a check-list of tactics for calibrating effort?

Yes. Many of them are similar to faith:

- Set small goals.

- Befriend meditators.

- Work with a teacher.

- Check-in with yourself. Ask yourself, “Do I look forward to meditation? Am I meditating simply and naturally? Am I enjoying meditation?” Don’t ask yourself every 5 minutes, rather only when it feels like things are a bit off and you want to check-in to see what’s going on.

- Change posture. If you’re very sleepy, do walking or standing meditation. If you’re listless, sit more upright, open your eyes, recenter yourself, and hold that posture. If you’re over exerting yourself or the mind’s racing, lay down. If you’re doing many sessions together on a retreat, then make sure you get some good cardio in throughout the day to keep your energy levels up and disperse the pent-up energy from hours of sitting.

- Segment/simplify the practice. If you’re overexerting yourself, there are two methods: 1) graded slowdown and 2) simplification. Graded slowdown means if you’re clamping down on the meditation object and burning with desire for meditation, you don’t throw on the brakes to stop it. Instead, you tell yourself to relax just a little bit. Then a little bit more. Then a little bit more. Until, step-by-step, you’ve relaxed your efforts. If you’re focusing on the breath, for example, the graded slowdown might mean counting every in-and-out breath or quickening the breath. After the mind’s slowed down somewhat, then you can just count the in-breath and slow the breath down. After it’s slowed even more, you can let go of counting and breath naturally.

The second method is more difficult but more effective: simplification. This is throwing the breaks on effort. If you’re following the breath, for example, don’t focus on a single point but relax the mind and feel instead the whole body as the breath passes in-and-out. Simplifying the practice will let the mind ungrip from the object.

On the other hand, if you’re feeling dull and listless, segment the practice. If you’re breathing, for example, be aware of the breath at multiple points or follow the breath in from the beginning to the end and back. Notice the breath every step of the way. Make different sensations of the breath increasingly clear. Segmenting forces the mind to work harder and, thus, combats lethargy.

Visualization of light. If you frequently struggle with sluggishness and drowsiness, take a break from your main object and visualize light instead. It might mean taking a week off to engage in this practice before going back, but it’s better than snoozing away that precious meditation time. - Resting the mind in open awareness. If you find yourself pressing your foot on the pedal too much for too long, take a break from your main object and switch to resting in open awareness, or shikantaza. This practice is impossible to effort and provides a powerful antitode to meditators who burn themselves out.

Mindfulness

There are two key aspects of mindfulness: 1) remembering and discerning what you should and shouldn’t be doing at a particular time and 2) applying awareness in line with 1. The role of memory and discernment makes mindfulness a better translation over awareness on its own. Mindfulness is always of a particular thing in a particular way, not simply being aware.

If you hear teachers say “be mindful without judgment” or some of that nonsense, ignore it. You can’t and shouldn’t be mindful without judgment. The mind receives a nearly unlimited supply of information at every given moment and without judgment we would be overwhelmed and paralyzed by it. It also happens to be nearly impossible.

To show you how this works, let’s do a short meditation. Are you down?

Got nothing better to do.

Same. Let’s begin by looking at the room. Be curious to see what’s here now. Take a few minutes to scan the various objects. Notice the surface of the wall, the little nicks and discolorations. Notice the floor. Notice the books on the shelves, their colors and titles, how they’re arranged. Soak in every detail without commentary or explanation. Just see.

Next, scan the room again and stop at an object that strikes your interest. Any object will do. Now, look at that object in close detail. What color is it? Is the color uniform or variegated? Are there any nicks, scratches, or other damage? What does its texture look like? If you can, hold it in your hand or run your fingers along its surface. Feel it from every angle.

What happened to your sense of sound while inspecting that item?

The sounds vanished into an indescribable fuzz.

Now take a moment and listen. What can you hear?

The crowing of roosters. A motorcycle riding past in the distance. A door closing shut. The hum of the AC.

All of those sounds vanished, though, when you focused on that item, correct? You weren’t sorting them out, identifying them, measuring the distance, and all of that, right?

Right.

And what about your awareness of what was around you while you inspected that item? Before, you noticed the chair, the fan in the corner, the trees bobbing gently outside, but after you focused on the item, where did your awareness of the room go?

It faded into the background like the sounds.

Precisely. This little exercise shows how mindfulness works. I gave you a particular object to be aware of and a series of tasks to complete. That directed your mind and filtered out irrelevant senses and thoughts. Your hearing diminished. Your sight narrowed. If you found yourself looking around, you knew it’s off task and reigned your attention back in. Were you aware? Yes, but you were also discerning. Awareness plus discernment is mindfulness.

Balance is necessary for mindfulness. If you become hyper focused on an aspect of experience, it’s an obstacle. If you become too relaxed and distracted by irrelevant sensations or thoughts, that’s also an obstacle. Mindfulness has to strike a balance between the different activities arising in the present. It’s difficult to quantify these things, but I’d put the numbers somewhere in this ballpark:

5% awareness of how you should meditate.

5% awareness of how you’re meditating.

90% awareness of your meditation object.

A mistake many meditators make is they try to be aware of only the meditation object and ignore the process of meditation itself, but can you imagine any task that you can do mindlessly and succeed at? If you’re fighting, you have to be aware of where you place your kicks, your footwork, how you’re reacting to your opponents strikes, what emotions are going through you, your game plan, the pre-drilled counters to his right hand, how you’re adjusting, and what works and what doesn’t. This knowledge isn’t the result of a long internal dialogue that’s going on during the fight, rather, it’s intuited or comes in flashes of thought. Meditation is no differet.

Balancing mindfulness means ensuring you keep a solid balance of 1) how you should be meditating, 2) how you’re doing it, and 3) the object of meditation. If you’re too self-conscious, like a fighter over thinking what’s going on, you’re no longer in the fight. If you’re not self-conscious enough, though, you might keep eating the same jabs by the defilements and make no adjustment. Right mindfulness is the sweet spot between.

Like with the other factors, you learn your sweet spot through regular practice, although there are a few tools to help you calibrate it.

- Befriend practitioners.

- Work with a teacher.

- Check-in with yourself. Ask yourself, “Am I clear about what I should and shouldn’t be doing? Am I clearly aware of how I’m meditating? Am I clearly aware of the meditation object?” The responses to these questions needn’t launch a flurry of thoughts. They can direct mindfulness towards those aspects of your experience or unleash a few flashes of thoughts before returning to the object. If things are going off the rails, however, it’s worth it to recollect yourself and spend some time strategizing how to fix the problem.

Once your mind settles into deeper meditative states, the percentage of focus on the meditation object will gradually increase, but that’s more advanced and needn’t be covered now.

Concentration

The practical distinction between concentration, or samadhi, and mindfulness is meaningful once a meditator can stay with a meditation object for ten minutes without any intrusive thoughts. Until that time, mindfulness and samadhi are largely indistinguishable.

Hopefully, though, you will discover that distinction for yourself. For when that time arrives, let me share this warning so you can keep it in your back pocket or use as a reference. The serenity from concentration is powerful and highly addictive. Once meditators can regularly access samadhi, they often turn into junkies, rushing off into concentration at any chance they get. This is better than binging on anime, but it also prevents the mind from developing the insight that leads to freedom and from more mundane things, like feeding their dogs or washing the dishes. Many practitioners spend years ensnared by the serenity of samadhi.

How do I prevent that?

As with every other factor, good friends and a teacher are key. If you’re going off the rails, they’ll keep you in check. Some meditators tell themselves, “Nah, I’m good. If things are going off the rails, I’ll know and I can reach out to someone, but I’m fine now.” The problem with this attitude is that when you’re going off the rails, you usually don’t know it. Instead, you think that you’re flying towards enlightenment at 1,000km/hour. As that view calcifies in the mind, it becomes more difficult to correct. I know monks who’ve spent 30 years living in the forest addicted to samadhi and puffed with pride. They’re some of the most insufferable humans I’ve ever met and it’s unlikely they’ll ever change their ways.

But it sounds like the teaching’s very clear: it’s both concentration and wisdom. Surely they’d eventually realize the error of their ways.

Nope. India is full of samadhi junkies who’ll spend their life blissing out. Their addiction blinds them.

Don’t worry, though, this is very, very rare and life-ruining addiction to samadhi happens almost exclusively to full-time contemplatives who have isolated themselves. If you’ve got a job, family, friends, and hobbies, it’s unlikely to be a big issue. The best protection against it, though, is having good friends and a good teacher to pull you back when you do go off the rails. The other correction for too much samadhi is vipassana, which is part of the next factor.

There are a few ways, though, for you to properly calibrate samadhi.

- Befriend practitioners.

- Work with a teacher.

- Check-in with yourself. Ask yourself, “Do I enjoy meditation? Are any hindrances present? Is the mind dynamic?” These questions will help identify any areas you’re stuck or the obstacles of samadhi.

- Vipassana meditation. If you find the mind’s becoming too still and listless, consider switching to vipassana meditation. Investigate your experience and take as your object the problem that’s here now. What does it feel like? Why does the mind fall into that state? How do you get out of it? The answers should primarily come from observation, not thinking. You can also use the other vipassana practices we’ll cover later.

- The Five Antidotes. The enemy of samadhi is the Five Hindrances. Keep track of these as you meditate and apply the antidotes when necessary. If you find yourself stewing in anger, switch to loving-kindness. If you find your mind jumping around wildly, come back to the breath. You shouldn’t jump around too much. If a hindrance is mildly bothering you, best to ignore it and stick to your original meditation object. However, if you find it keeps dragging your mind away then it’s better to meditate on its antidote for the rest of the session or even a few days until it clears up. A word of caution, though. You shouldn’t meditate using more than 2 objects over the course of one session. Keep meditation to either the main object or the antidote. If you jump around too much, it’s going to be very difficult for it to settle down and for you to develop real mastery of the meditation object.

Wisdom

There are two types of wisdom: theoretical and applied.

Theoretical wisdom is the abstract, intellectual understanding of meditation and it is extremely important. Theoretical wisdom includes knowing the Five Forces, the Five Hindrances, the Five Antidotes, and how the Three Trainings (Morality, Concentration, and Wisdom) relate to each other and are put into practice. If you clearly understand the theory, then it becomes much easier when dealing with issues when they arise.

To see how important theoretical knowledge is, look at the distinction between serenity and insight. It seems obvious to many practitioners in the 21st century now, but that’s because it’s permeated the spiritual zeitgeist. Look up the weizzas in Burma or the reusee of Thailand to see how a contemplative tradition can go astray without this distinction. These two groups have extremely strong meditators, but their focus is on achieving magical powers and immortality. There has been no insight tradition until the recent revival of Buddhist scholarship. Studying and contemplating on this topic for just 30 minutes, though, could save someone a life-time of misguided practice.

Couldn’t they just figure it out themselves, though?

It’s possible, but a look at the history of contemplative traditions says otherwise. Understanding these concepts saves time, but it’s also an ongoing process.

After our conversations, for example, even if you 1) remember the theory and 2) understand its spirit and the reasons behind it, that understanding is limited by your own experience and the understanding you have now. As you study and practice more, your understanding will grow more refined and, with it, your ability to apply that theory to the conundrums which life throws at you.

Applied wisdom is the wisdom that arises from practice. You might, for example, know that adequate rest is important for meditation, yet you won’t understand the nuance and details of it until you’ve meditated on a few hours of sleep. Once you have enough experience, you intuitively understand its importance and will easily choose to sleep in instead of trying to wake-up early to squeeze in an hour of sleepy meditation.

Applied wisdom, like theoretical wisdom, is an ongoing process. After you realize that forcing yourself to wake-up early for a drowsy morning meditation, you might later discover that if you hold onto that shred of wakefulness when you first rise in the morning that you can meditate well despite exhaustion. This won’t make sense to you now, just like it won’t make sense to you if an Olympic runner is precisely describing how to place your feet to maximize efficiency while running. The words are incomprehensible because they don’t connect to your experience. As your meditation skills improve, you’ll notice what that “shred of wakefulness” is and how to hold onto it to power through exhaustion. This process of refining understanding continues until the day you die.

How do you develop the different types of wisdom?

You develop theoretical wisdom by studying books, talking with friends, and from reflecting on your own experience. By reflecting on all three of these, you develop a theoretical understanding of how to meditate.

Memory gets a bad wrap in our culture, but it’s important no matter what you’re doing. Whether you’re in business or hosting a meeting, having a strong memory will help you succeed. In business, you should remember the principles of sound investing, what factors are driving the market, who the competitors are, how they compare to your company, the reports and suggestions of staff and consultants, and your own experiences as a business owner. If you don’t have a sharp memory, it’s going to be impossible to hold all of this information in your mind simultaneously while re-strategizing with the management team. When situations arise that require immediate action, you’ll have poor information to guide your and, thus, make worse on-the-spot calls. Memory is important in business and, for the same reasons, is just as important in meditation.

I suggest you memorize Zen’s key principles, strategies, and tactics. Not only will memorizing strengthen your memory and serve you well in other areas of your life, but it will also be invaluable when problems arise in your spiritual life. In real life, you can’t open google or flip through a book when a friend asks you to lie for them in a meeting or if anger overwhelms you because someone cuts you off on the freeway. You have to decide then-and-there and knowing the core values, strategies, and tactics will help you to respond rightly.

You develop applied wisdom by meditating while also monitoring and reflecting on your experience. Many teachers vilify the mind as something that should be shut down. Wrong. If you take that approach towards your mind, you’ll make an enemy of an ally. Some degree of self-consciousness will help you learn from your mistakes and make adjustments in the future. For example, if you fry your nerves pushing to stay with the breath, monitoring yourself during that process will help you understand what’s going on and why it’s happening. With that information, you can problem solve. Often, the problem solves itself once you observe it happening in real time. Sometimes you have to sit and think about it. Both of these increase Meditator IQ. The higher the IQ, the easier it is to recognize and nip problems in the bud when they arise.

The final aspect of wisdom is vipassana-bhavana, or insight meditation.

Vipassana-bhavana directly investigates the nature of reality. Samadhi supports vipassana-bhavana because it lets the mind see clearly. Vipassana-bhavana helps samadhi because it loosens the hold of the attachments that disturb the mind. A balanced practice requires both of these.

How do I divide time between these two?

It depends on the person and the practice. For beginners, 80% samatha and 20% vipassana. Establishing concentration’s more important at first because without it insight is shallow. Absent stillness, vipassana practice devolves into dullness and thinking about reality rather than experiencing it. Once a meditator has stable concentration, he can focus on vipassana without losing effectiveness.

If you meditate 30 minutes a day, seven days a week, consider spending two sessions a week on vipassana and five on samatha. That ratio’s more than 20%, but it’s better than one day a week. Switching it up like this will also prevent either the vipassana or samatha sessions from feeling too dry and predictable.

And how do I develop wisdom?

There are a few ways.

- Good friends.

- Work with a teacher.

- Reflect. Spend some time reviewing what’s working and what needs work. Analyze the reasons behind each and ways to maintain the good and fix the bad. I suggest every few days check in with yourself and ask these questions. Just two or three minutes should suffice. Once a month, spend a good 20 or 30 minutes going through these questions in detail and take stock of your progress. It’s especially effective if you’ve set a goal, as you can then see how well you’re progressing and what adjustments need to be made.

- Study. Take time to review Zen theory and practice. A firm intellectual understanding helps when you face difficulties and make decisions. Memorizing the main theory is even better, as it means that it’s ready to be used when needed at all times. Otherwise, the knowledge will just stay on the page instead of being applied to one’s life. For most meditators, I suggest a lot of study at the beginning

- Live your life. Care must be taken, though, that one’s not too reflective. If you find yourself intellectualizing too much and overthinking, it’s time to turn the volume down. Take a break from books, especially spiritual books. Reading feeds the intellectual appetites and will rear its head in meditation and daily life. Also, spend less time reflecting on yourself or problems that your facing. Instead, find other activities that ground you, like music, art, or exercise.

- Samadhi. If you’re restless and thinking instead of directly observing, your concentration is lacking. In that case, spend some time focusing on your main meditation object. As with the antidotes, you shouldn’t switch too frequently. If your vipassana session is going off the rails because of overthinking, then best to go back to your main object for the entirety of the session and perhaps a few more before coming back to the vipassana object.

This is a lot!

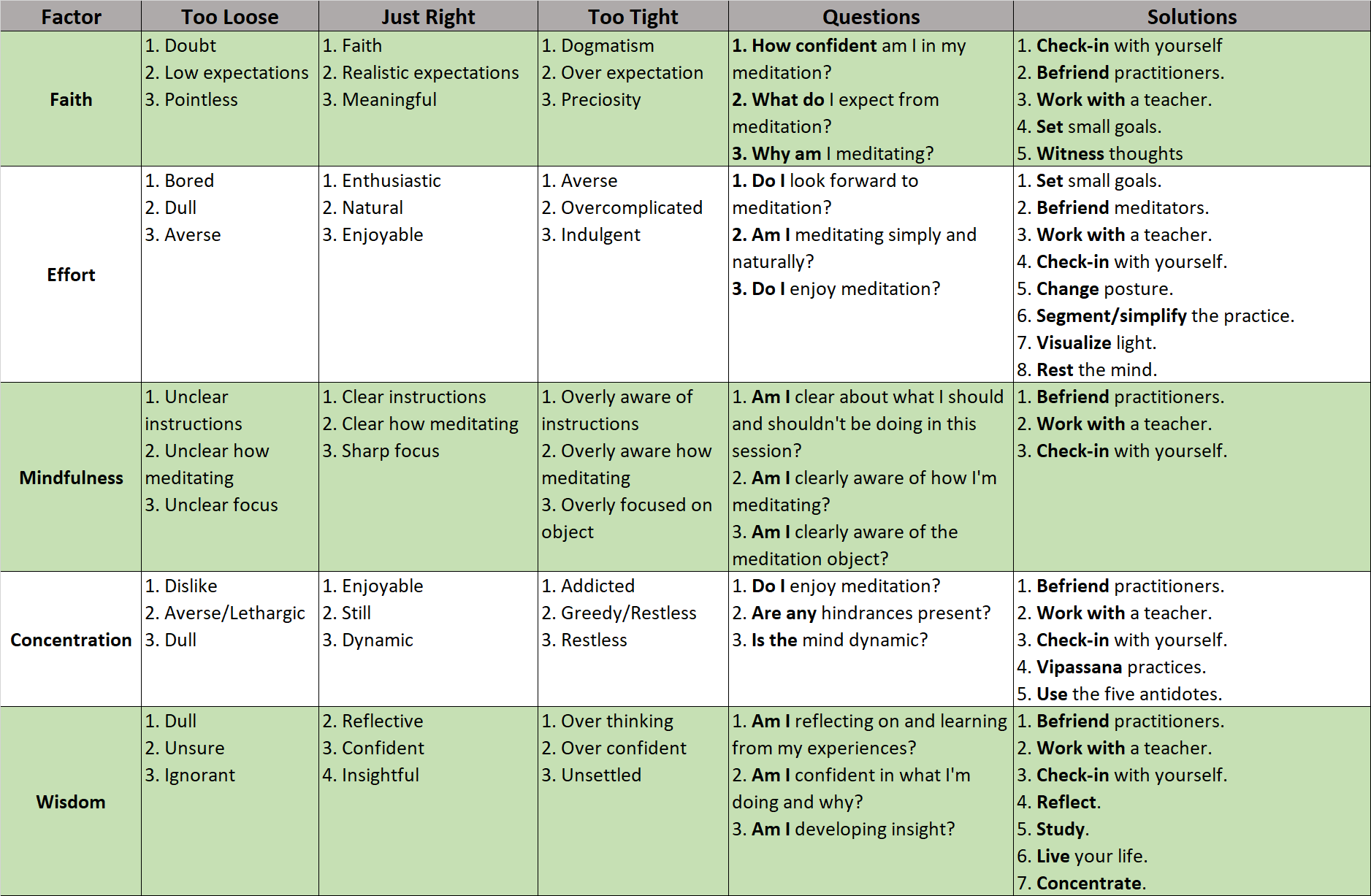

It is, but if you find yourself in trouble, these factors and the calibration tools will prove invaluable. Keep these in mind, keep adjusting them, and keep on practicing. Above we went into a lot of detail, so here's a chart to summarize the main points to refer back to. If you keep these Five Factors properly tuned, you’ll do well in your meditation whatever the object.

References:

- "Appativana Sutta: Relentlessly" (AN 2.5), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an02/an02.005.than.html.